|

| Men of Steel: Henry Cavill and Christopher Reeve portray Superman, 35 years apart. |

"He's the hero Gotham deserves, but not the one it needs right now."- Commissioner Gordon describing Batman in The Dark Knight

Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist Mary McGrory is credited with one of the all-time great quotes about sports: "Baseball is what we were, and football is what we have become."

History has more than vindicated Ms. McGrory's statement. The ratings for the 2012-2013 television season have just recently been tabulated, and the leader -- by a wide margin -- was NBC's Sunday night NFL telecast. A mere eight years before my own birth, there was no such thing as the Super Bowl. Now it's a de facto Holy Day of Obligation. Football has long since blitzed past baseball to become America's true national pastime, and I think the reason for that has a lot to do with a gradual shift in the collective American psyche over the last few decades.

In short, we've become more cynical, more technical and less optimistic in recent times. In the years since 9/11 especially, we've become a paranoid, anxious nation, thirsty for blood and hungry for flesh. Football is the sport, more than any other, that fuels our aggregate psychosis. It's a dark game for dark times. Baseball, meanwhile, seems fairly musty in comparison. It's not even a contact sport, for crying out loud!

George Carlin famously explained the differences between these two sports better than I ever could, so I think I'll let him do so now.

So what does any of this have to do with Superman? Well, it's like this, citizens: Superman is the baseball of superheroes. He's corny. He's old-fashioned. He's pastoral -- the very term George Carlin used to describe baseball. Though born on the far-off, doomed planet of Krypton, Superman grew up as Clark Kent amid the pastures of Smallville, the isolated cowtown where his adoptive parents, Ma and Pa Kent, raised him with the good Christian values of the Middle West.

Superman's origin story has often been interpreted as a variation on the Nativity with Clark as an all-American version of the Christ child. Even the Kents' first names -- John and Martha -- are reminiscent of Joseph and Mary. Little wonder, then, that Superman has often been portrayed as the ultimate square, a goody-two-shoes as wholesome as a glass of milk and just about as interesting.

Meanwhile, poor Supes has been eclipsed in the minds (if not hearts) of the public by Batman, a fellow DC hero and frequent teammate. Batman's origin is rooted in urban violence: he saw his own parents gunned down by a mugger and ultimately decided to avenge their deaths by becoming a costumed vigilante. The famed "Caped Crusader" has been portrayed in wildly diverse ways and with greatly varying degrees of seriousness since his debut in the fateful year of 1939, but for the last quarter-century or so, Batman has largely been depicted as a deeply troubled, morally conflicted loner who has chosen to fight crime for reasons that are far from healthy.

This is the character America has embraced, and I think his ascendancy mirrors that of professional football. Batman is a flawed, gloomy pseudo-savior for these sick times of ours. No wonder we love him.

Five summers ago, the most lauded of the studio blockbusters was Christopher Nolan's The Dark Knight. The most ridiculed was Steven Spielberg's Indiana Jones and the Crystal Skull. Is it sacrilege to say that I had more fun at the latter than the former? I emerged from The Dark Knight feeling woozy and a little depressed, like I'd just spent two-plus hours in a tumble dryer, while at least I came out of Crystal Skull feeling like I'd seen the adventure yarn that I'd paid for.

I think the real problem with Spielberg's film is that Indiana Jones was simply the wrong man for the audiences of 2008. It's difficult to imagine him brooding as he stares into a hopeless gray sky. Certainly, Crystal Skull is absurd and cheesy. But what audiences forgot (or ignored) was the fact that absurdity and cheesiness were in the character's DNA from the very beginning of the franchise. After you've found the Ark of the Covenant and the Holy Grail, where else is there to go but aliens from outer space?

Fans howled at the improbability of Professor Jones surviving a nuclear blast by hiding in a refrigerator, but is this really any more ridiculous than the melting Nazis of the first film or the invisible bridge of the third?

While the online community was grumbling about how preposterous Crystal Skull was, they were also rhapsodizing about the supposed realism of The Dark Knight. This argument struck me as baffling for several reasons. First, Nolan's film is in no way realistic. It's not even close. Insane, physically impossible events happen throughout the entire running time. This is not mere conjecture on my part, either. It's scientific fact. If Bruce Wayne really put on that rubber bat suit, he'd barely be able to walk around, let alone win any fights. And if he tried that gliding technique with his cape, he'd soon wind up as an omelette on the sidewalks of Gotham City.

But beyond that is a more troubling question: why would we even want a superhero movie to be realistic? Perhaps our imaginations have been defeated or deflated by years of reality television and grim headlines. Figuratively speaking, we have sequestered ourselves in one dismal, little, windowless room while great halls remain cordoned off and unexplored. Kind of sad, really, but understandable and perhaps inevitable.

This is the world Superman now enters in 2013. A football world. A Batman world. The character's latest cinematic reincarnation, Zack Snyder's Man of Steel, faces critics and audiences on June 14, 2013. The presence of Christopher Nolan as a producer suggests that the film will take a darker, grittier, more reality-bound approach to the character. These suspicions are confirmed by the film's trailer, in which Clark Kent/Superman appears to be dour and humorless, his powers as much a burden as a blessing.

For a while in the 1970s and 1980s, Christopher Reeve managed to find a manageable middle ground with the character. His Superman had a sense of humor, certainly, but was not a cartoonish clown or a novelty act. Furthermore, he had a touch of old-fashioned romance but did not sacrifice his masculinity in the process. Best of all, he made it look like being Superman -- while occasionally a trial -- was a hell of a lot of fun. To my mind, Reeve is the only actor to truly understand the character and play the role properly. Every other actor has either been too stiff and serious (Brandon Routh in Superman Returns) or too much of a lightweight to be a credible action hero (Dean Cain in Lois & Clark).

I plan on seeing Man of Steel, but I worry that the character has lost something essential in the process of being remade for the audiences of 2013.

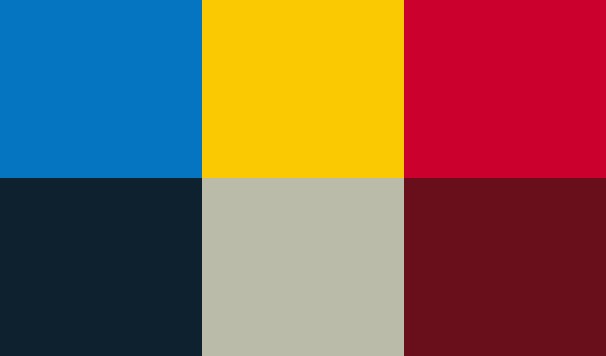

More than anything in the plot or dialogue, I am concerned about the movie's appearance. Superman comes from comics, an entirely visual medium, and has been transplanted to film, a primarily visual medium. A movie, more than anything else, is a Thing To Look At. So what has Zack Snyder provided us to see here? Obviously, in any Superman movie, the main point of visual interest is Superman himself. I was struck by how different Henry Cavill's 2013 uniform was from the one worn by Christopher Reeve in 1978. Here's a color chart breakdown of the two:

|

| A color chart comparing the Superman uniforms of 1978 and 2013. Notice a difference? |

|

| Captain Kirk and his bumpy new uniform |

If you study the picture at the beginning of this article, in addition to the color change, you'll also notice a change in the texture of the material. Whereas Reeve's leotard was smooth and seamless, Cavill's outfit is ridged and porous.

This emphasis on hyper-accurate detail, perhaps an outgrowth of high-definition television and digital theater projection, is not exclusive to Superman. The trend began, I believe, with Spider-Man about a decade ago. Now, every fantasy hero -- including Captain Kirk -- has to wear such an outfit. Again, I am a little wary of this. Screen heroes should, in some sense, be abstract and mysterious. The new fabric makes these characters more plausible, perhaps, but it also takes away some of the fun because it subtly drags them down to the level of practical reality. I have plenty of practical reality all around me. Why do I need more of it in a superhero movie?

At the end of Oliver Stone's biopic Nixon, the disgraced politician -- a pessimist saint if ever there was one -- looks up at a portrait of his one-time rival, John F. Kennedy and says, sadly: "When they look at you, they see what they want to be. When they look at me, they see what they are."

Can't we say the same about our movie heroes? Superman is who we want to be (or used to want to be), and Batman is who we are (or fear we are). We used to look to the silver screen to see characters who were impossibly idealized and embodied our fondest hopes and dreams. Now, I suppose, we want to look up there and see at least something of ourselves -- our flawed, fallible selves -- projected on the wall. In a few weeks, we'll see how well Man of Steel accomplishes that.