|

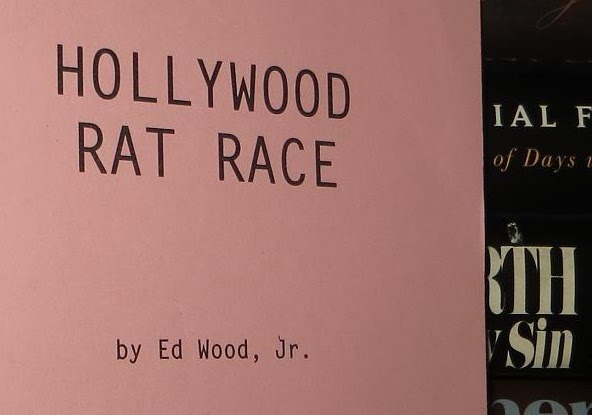

| Hollywood Rat Race was published 33 years after it was written... and 20 years after its author had died. |

"Who are these people who hate Hollywood? Perhaps a bunch of communists?"

-Edward D. Wood, Jr.

|

| John Huston with the cast of 1982's Annie. |

Take the great John Huston as an example. He directed some of Hollywood's all-time classics in the course of his 46-year career, including The Maltese Falcon (1941, his directorial debut!), The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948), and The African Queen (1951). Working as an actor and director until 1987, the year of his death, Huston helmed some well-received films in his final years, such as Prizzi's Honor (1985), The Dead (1987), and Under the Volcano (1984).

But that last decade also included one of Huston's most-puzzling, least-characteristic projects: Annie (1982), the expensive, gaudy, and utterly frivolous adaptation of a successful Broadway musical, which in turn was based on a long-running comic strip. The film barely earned back its then-astronomical $50 million budget and was considered a letdown for Columbia Pictures.

Many critics, including Roger Ebert, wondered what a respected dramatic director like Huston was doing with this silly cotton candy musical. But there's his name in the opening credits just the same. Huston even does a bit part as a radio actor, adding his own personal signature to the film in that manner. So when you sit down to watch Annie, you are witnessing not only a chapter of John Huston's autobiography but a snapshot of popular culture in 1982. Whether you end up liking the film or not (I can't wholly endorse it but feel the film has its merits), Annie does have value as a historical document. All movies do, to one degree or another.

Consciously or not, each film documents its own making as well as the era that brought it into being. We sometimes talk about separating "the artist" from "the work," but perhaps this is not possible or even advisable. An artist's life and work are conjoined twins. That is what I have learned in my study of Ed Wood's singular career in Hollywood. Even apart from the blatantly autobiographical Glen or Glenda? (1953), Ed Wood's screenplays and novels reflect the man's experiences, fears, obsessions, and tastes.

This is especially clear in the case of one posthumously published manuscript which was intended as an insider's guide to Hollywood but now reads like a case study in Ed Wood-ology 101. Of course, I am referring to...

HOLLYWOOD RAT RACE

(written circa 1965; published 1998)

Alternate titles: None.

Availability: Hollywood Rat Race (Four Walls Eight Windows, 1998; Da Capo Press, 1999) is still easy to acquire and quite affordable.

The backstory: "When I took on this project, I wanted to reminisce as well as get the point across as to what it's really like in my Tinsel Town." So wrote Edward Davis Wood, Jr. in Hollywood Rat Race, a most curious manuscript he penned during the LBJ years but which did not actually see publication until 1998, a full two decades after his death. The available edition has no introduction or explanatory notes, so relatively little is known of its existence. From clues in the text, however, it seems all but certain that it was written circa 1965. Ed mentions that he arrived in Hollywood in 1947 and has been there 18 years. He also mentions that the moon landing will occur in four years and repeatedly references the film Orgy of the Dead (1965) as being a new release.

The fact that the manuscript survived at all is a minor miracle, considering that many of Ed's personal belongings were thrown away during his sad and tumultuous final years as he slipped further into obscurity, poverty, and alcoholism. The book's edition notice grants a copyright to the "Estate of Edward D Wood, Jr.," and the photo of Ed on the back cover was supplied by his widow, Kathy, so evidently she either discovered this book among her late husband's personal effects or merely held onto it until she could find a publisher.

The book is partially a how-to guide for aspiring actresses and actors (mainly the former) who hope to move to Hollywood and break into the motion picture business. Most of his advice boils down to two oft-repeated words: "stay home." Essentially, he advises young starlets to try to get acting and modeling work near their own hometown because work is tough to come by in Tinsel Town. Newcomers will find that there's a lot of competition for each assignment. Living expenses are high in Hollywood, and the town isn't as glamorous as it used to be anyway.

For those who insist on coming to Hollywood, Ed has a few bits of practical advice. He says to be wary of sleazy scam artists, phony screen tests, disreputable beauty contests, and lustful movie producers who just want to get into your angora sweater (literally). He recommends getting professional headshots and says that screen actors will likely need an agent and a publicist if they're going to make any headway in the industry.

Along the way, Ed manages to work in many details about his own life and career, including anecdotes about his films and the actors and actresses who starred in them. There are tidbits here about Criswell (pg. 20 and pg. 138, both about going to the Brown Derby with the famed psychic), Lyle Talbot (pg. 50), Tom Keene (pgs. 66-68), Kenne Duncan (pgs 104-105), plus the story of a truly harrowing accident which occurred on the set of one of Bud Osborne's westerns (pgs. 57-60).

Above all, though, Eddie's thoughts were with Bela Lugosi when he wrote this book. "A personal weakness stole his life and his fortune," Ed writes euphemistically on page 32, "but not his talents." By far, the book's single-longest showbiz anecdote (pgs. 93-104) concerns a personal appearance Bela made at a movie theater in San Bernadino, CA, accompanied by Ed Wood and Dolores Fuller (identified here as Bela's "lovely assistant" and a "motion picture actress in her own right" -- this was more than a decade after she and Eddie had split up).

Apparently, Bela was forlorn because his movies were making a splash on television, yet younger viewers didn't know whether he was alive or not. So Eddie decided that a personal appearance was the cure and set up the date for Bela, who was nervous because he had no "act" to speak of. But the appearance was a smash success, leading to Bela's own comedic Las Vegas revue (written by Eddie), which was contracted for four weeks but ran seven. "This was February of 1954," Ed writes, "so close to the end of Bela's life." You get the feeling Ed was proud of having the opportunity to give his hero, Lugosi, one last hurrah.

Speaking of which, elsewhere in Hollywood Rat Race, Ed dishes on the making of Plan 9 from Outer Space, although he still clearly prefers the title Grave Robbers from Outer Space. He confirms most of the usual bits of Wood-ian trivia (pgs. 118-120). Yes, the film was funded by Baptists. Yes, he and Tor Johnson were baptized in a swimming pool. And, yes, the script was written around footage of Bela Lugosi which had been shot for another project entirely. What I didn't know is that the infamous "Solarnite bomb" was a late-arriving inspiration which Eddie didn't conceive until the eighth day of a twelve-day shooting schedule (pg. 128). Ed also lets us know that Bride of the Monster was inspired, as one might guess, by a dream, while Final Curtain was written originally as a short story while Ed was studying drama in Washington D.C. (both pg. 125).

It's also rather amusing to learn (on pgs 115-116) that he thought Orgy of the Dead "looked pretty bad" when he was on the set but turned out great thanks to its director (Stephen Apostolof, not mentioned by name) and "could well become a classic" in its genre. As indeed it has... at least to me.

Perhaps most valuably, this book sheds some light on some of the lesser-known eras of Ed Wood's career. For instance, he discusses his campaign work for controversial LA mayor Sam Yorty (pg. 46; pg. 130). He fills us in on his stint making technical documentaries for the Autonetics technical research facility in the early 1960s (pg. 129). And he mentions any number of lost or forgotten projects, including a novel called The Inconvenient Corpse, a book inspired by character actor Jack Norton, who specialized in playing drunks but who sadly died before getting to read it (pg. 34). Most fascinatingly, on page 69, Ed tells us he wrote three films (The Gunslinger, War Dance, and Double Noose) for Tom Keene, the bland cowboy actor who had played an insurance investigator in Ed's Crossroad Avenger and who went on to be a real-life insurance salesman when his film career petered out. Wonder whatever happened to these?

The reading experience: Pure Eddie. The first mention of angora sweaters arrives on page four, and there are many to follow. Those looking for classic Ed Wood quotes will find many sentences in this manuscript which are written in his signature style -- stilted and convoluted, yes, but also strangely poetic. A few favorites:

With lines like that, it's kind of a shame that Criswell wasn't around in 1998 to record the book on tape version of Hollywood Rat Race. Actually, this book is quite sensible and reasonable for the most part, other than some truly egregious references to angora sweaters... and one green taffeta dress (pg. 97). Well, there is one truly nutty suggestion. In a chapter called "How to Live in Hollywood Without Money," he semi-seriously advises his readers to sleep in Griffith Park (coincidentally, the location for "Lake Marsh" in Bride of the Monster).

It's hard to divine Ed Wood's true feelings toward Tinsel Town, as they change throughout this book. In a chapter called "Hate," Eddie rails against Hollywood's "haters" (half a century before that become a popular slang term) and says that those who complain about the town are likely to be commies (pg. 105). Just five pages later, though, he's more pragmatic: "Ah, our world, as well as my town is changing...and it's all because we're growing up." Throughout Hollywood Rat Race, there are references to the fact that androgynous "beatniks" are taking over the once-glamorous Sunset Strip, which would become a key plot element in Death of a Transvestite (1967).

By the end of the book, in a chapter simply called "Hollywood," Eddie's mood has become apocalyptic. He states on page 136: "Actually, there is no Hollywood any longer. It's become a kaleidoscope of meaningless ectoplasms which abound between reality and the unreality." He ends the book two pages later with this ultimate pronouncement: "That's the Hollywood as an insider knows it. Trouble. Problems. Heartache. Believe it or not, your life is more real than the Hollywood scene." Kinda makes you want to catch the next Greyhound bus headed west, doesn't it?

And now, I think it's as good a time as any to cover one of Ed's most obscure little films, since he mentions it rather prominently in Hollywood Rat Race.

TRICK SHOOTING WITH KENNE DUNCAN

|

| An uncorrected proof of Ed Wood's Hollywood Rat Race. |

|

| Ed's posthumous work. |

Availability: Hollywood Rat Race (Four Walls Eight Windows, 1998; Da Capo Press, 1999) is still easy to acquire and quite affordable.

The backstory: "When I took on this project, I wanted to reminisce as well as get the point across as to what it's really like in my Tinsel Town." So wrote Edward Davis Wood, Jr. in Hollywood Rat Race, a most curious manuscript he penned during the LBJ years but which did not actually see publication until 1998, a full two decades after his death. The available edition has no introduction or explanatory notes, so relatively little is known of its existence. From clues in the text, however, it seems all but certain that it was written circa 1965. Ed mentions that he arrived in Hollywood in 1947 and has been there 18 years. He also mentions that the moon landing will occur in four years and repeatedly references the film Orgy of the Dead (1965) as being a new release.

The fact that the manuscript survived at all is a minor miracle, considering that many of Ed's personal belongings were thrown away during his sad and tumultuous final years as he slipped further into obscurity, poverty, and alcoholism. The book's edition notice grants a copyright to the "Estate of Edward D Wood, Jr.," and the photo of Ed on the back cover was supplied by his widow, Kathy, so evidently she either discovered this book among her late husband's personal effects or merely held onto it until she could find a publisher.

The book is partially a how-to guide for aspiring actresses and actors (mainly the former) who hope to move to Hollywood and break into the motion picture business. Most of his advice boils down to two oft-repeated words: "stay home." Essentially, he advises young starlets to try to get acting and modeling work near their own hometown because work is tough to come by in Tinsel Town. Newcomers will find that there's a lot of competition for each assignment. Living expenses are high in Hollywood, and the town isn't as glamorous as it used to be anyway.

For those who insist on coming to Hollywood, Ed has a few bits of practical advice. He says to be wary of sleazy scam artists, phony screen tests, disreputable beauty contests, and lustful movie producers who just want to get into your angora sweater (literally). He recommends getting professional headshots and says that screen actors will likely need an agent and a publicist if they're going to make any headway in the industry.

|

| A last hurrah: Bela Lugosi in Plan 9. |

Above all, though, Eddie's thoughts were with Bela Lugosi when he wrote this book. "A personal weakness stole his life and his fortune," Ed writes euphemistically on page 32, "but not his talents." By far, the book's single-longest showbiz anecdote (pgs. 93-104) concerns a personal appearance Bela made at a movie theater in San Bernadino, CA, accompanied by Ed Wood and Dolores Fuller (identified here as Bela's "lovely assistant" and a "motion picture actress in her own right" -- this was more than a decade after she and Eddie had split up).

Apparently, Bela was forlorn because his movies were making a splash on television, yet younger viewers didn't know whether he was alive or not. So Eddie decided that a personal appearance was the cure and set up the date for Bela, who was nervous because he had no "act" to speak of. But the appearance was a smash success, leading to Bela's own comedic Las Vegas revue (written by Eddie), which was contracted for four weeks but ran seven. "This was February of 1954," Ed writes, "so close to the end of Bela's life." You get the feeling Ed was proud of having the opportunity to give his hero, Lugosi, one last hurrah.

Speaking of which, elsewhere in Hollywood Rat Race, Ed dishes on the making of Plan 9 from Outer Space, although he still clearly prefers the title Grave Robbers from Outer Space. He confirms most of the usual bits of Wood-ian trivia (pgs. 118-120). Yes, the film was funded by Baptists. Yes, he and Tor Johnson were baptized in a swimming pool. And, yes, the script was written around footage of Bela Lugosi which had been shot for another project entirely. What I didn't know is that the infamous "Solarnite bomb" was a late-arriving inspiration which Eddie didn't conceive until the eighth day of a twelve-day shooting schedule (pg. 128). Ed also lets us know that Bride of the Monster was inspired, as one might guess, by a dream, while Final Curtain was written originally as a short story while Ed was studying drama in Washington D.C. (both pg. 125).

It's also rather amusing to learn (on pgs 115-116) that he thought Orgy of the Dead "looked pretty bad" when he was on the set but turned out great thanks to its director (Stephen Apostolof, not mentioned by name) and "could well become a classic" in its genre. As indeed it has... at least to me.

|

| Jack Norton. |

The reading experience: Pure Eddie. The first mention of angora sweaters arrives on page four, and there are many to follow. Those looking for classic Ed Wood quotes will find many sentences in this manuscript which are written in his signature style -- stilted and convoluted, yes, but also strangely poetic. A few favorites:

- The atomic bomb didn't just happen. Many people of many trades, skilled people of long apprenticeship and longer study were commissioned for such a magnificent undertaking. (page 62)

- I liked the television series The Bell Brothers starring the Bell Brothers. (page 79)

- Sex! It becomes all important. Sex! (page 79)

- It's not the dark I fear -- it's the things that move around in it! (page 89)

- By 1953, the baby art called television was a baby no longer, but a skeleton filling out toward the giant it was to become. (page 93)

- Writing fiction is great fun. It's much like God creating his world and his people, putting them in a situation, then directing their every movement. (page 128)

|

| One of Criswell's books |

It's hard to divine Ed Wood's true feelings toward Tinsel Town, as they change throughout this book. In a chapter called "Hate," Eddie rails against Hollywood's "haters" (half a century before that become a popular slang term) and says that those who complain about the town are likely to be commies (pg. 105). Just five pages later, though, he's more pragmatic: "Ah, our world, as well as my town is changing...and it's all because we're growing up." Throughout Hollywood Rat Race, there are references to the fact that androgynous "beatniks" are taking over the once-glamorous Sunset Strip, which would become a key plot element in Death of a Transvestite (1967).

By the end of the book, in a chapter simply called "Hollywood," Eddie's mood has become apocalyptic. He states on page 136: "Actually, there is no Hollywood any longer. It's become a kaleidoscope of meaningless ectoplasms which abound between reality and the unreality." He ends the book two pages later with this ultimate pronouncement: "That's the Hollywood as an insider knows it. Trouble. Problems. Heartache. Believe it or not, your life is more real than the Hollywood scene." Kinda makes you want to catch the next Greyhound bus headed west, doesn't it?

And now, I think it's as good a time as any to cover one of Ed's most obscure little films, since he mentions it rather prominently in Hollywood Rat Race.

TRICK SHOOTING WITH KENNE DUNCAN

(1952? 1961? mid-1960s?)

Alternate title: Kenne Duncan: The Face That is Known to Millions of TV and Western Movie Fans. The title under which this film is commonly known, i.e. Trick Shooting with Kenne Duncan, appears nowhere in the credits and seems to have been bestowed upon it ex post facto, possibly for DVD release.

Availability: The DVD collection Big Box of Wood (S'more Entertainment, 2010)

|

| A smiling Kenne Duncan |

No one seems to agree exactly when Eddie and Kenne made this short promotional film for Remington firearms. The IMDb has it as 1961. A very good Ed Wood tribute site places it in 1952, a fact repeated by Rob Craig's excellent book, Ed Wood: Mad Genius. But Ed himself talks about the Remington film in Hollywood Rat Race, which likely was written in 1965. As Wood states on page 105: "In 1951 Kenne even rode Emperor Hirohito's white horse down Tokyo's main street and he has color newsreel film to prove it. We recently used this footage in a film about Kenne's act." This tells me that the Japanese footage in Trick Shooting is from the early 1950s but that the rest of the movie was probably not made until the 1960s. Therefore I'm guessing the IMDb's date is closer to the truth.

|

| Kenne shoots Necco wafers just to watch 'em die. |

The film sets up its pattern early, then repeats it over and over. In an unenthusiastic voiceover, Kenne tells us about some trick shot that he's going to perform, which almost always involves hitting a Necco wafer carefully positioned inside a small booth, then he does the trick shot successfully, we hear a metallic "PING!" on the soundtrack, and the process begins anew. Occasionally, he'll stop to give a pitch for Remington directly to the camera.

Throughout the film, there are cutaways to stills and posters from Kenne's movies (all obscure cowboy flicks) and personal appearances. It's like they're constantly trying to convince us that this guy is a star. His sharpshooting act, while impressive in a purely theoretical sense, is not very visually appealing. The infamous Japan footage arrives about eight minutes into this nine-minute movie, and it's not in color, as Ed had promised. It is rather amusing, though, to hear the Japanese newsreel announcer say the name "Kenne Duncan," which sticks out like a hot coal from the rest of his speech.

I guess the main point of interest for me, other than Kenne's "rhinestone cowboy" outfits, was the fact that his targets were Necco wafers. Kenne likes these because they shatter so well when shot, but for many Catholic kids, these candies are used as playtime substitutes for the eucharist wafers, lending the film a slightly sacrilegious air. Anyway, Kenne must have gotten tired of shooting candy wafers at state fairs, because he committed suicide by barbiturate overdose in 1972. His wake was held by the pool at Ed's place, with mourners delivering their eulogies from the diving board. I'd like to think Necco wafers were served -- or used as targets in a 21-gun salute.

Next week: I promised that once August was over, I'd jump back into Ed's movies. Guess what? I lied. You see, Ed wrote some short stories, too, and I want to devote at least one week of this series to those, since I've now gotten to read a few of them. Let's meet back here in seven days and talk all about it, huh?