|

| The conjoined Hilton sisters in Chained for Life. |

It is now time to turn our attentions to George Moskov (1893-1970). Never heard of him? You're forgiven. His filmography tells the story of yet another hardworking foot soldier of the mid-20th century movie industry, in which he worked mostly

"below the line" as they say in Hollywood.

In a bizarre coincidence that I swear is not meant to capitalize on recent headlines, Mr. Moskov is Ukrainian by birth. Way back in 1932, in fact, he wrote a Croatian-language film called

Ljubav i strast (which translates as

Love and Passion) for an outfit called Yugoslavian Pictures, Inc. Other than this early outlier, his credits are largely confined to the 1940s, '50s, and '60s. Along the way, George worked as a producer, writer, and second unit director, but most of his career was spent as a production manager, making sure that various small-time film productions operated on-schedule and on-budget.

About a week ago, I heard

an interview on the Projection Booth podcast with a producer-director named Larry Cohen (

It's Alive, The Stuff, Maniac Cop), who said he usually paid his production managers to stay home and out of his hair. Then why have them on the payroll at all? Union requirement, explained Cohen. But George Moskov seems to have been one of the good, reliable ones in the biz, lasting over 30 years and encompassing all kinds of films, from a Western with Ronald Reagan (1955's

Tennessee's Partner) to an entry in the

Charlie Chan franchise with

Sidney Toler and

Mantan Moreland (1944's

Charlie Chan in the Secret Service). Moskov seems to have worked on plenty of low-budget crime dramas but wasn't tied to any particular genre or subgenre. He only directed one feature -- the penny-ante flick we're covering this week.

For fans of outre cinema, Moskov's most intriguing credit is probably

Chained for Life (1952), for which he is listed as both a producer and a production manager. This rather notorious film, directed by Harry L. Fraser (whom I discussed a bit in my article on

The Bride and the Beast), was a never-to-be-repeated vehicle for Violet and Daisy Hilton, the conjoined twin sisters from

Freaks (1932). It is from a book about the Hilton sisters, Dean Jensen's

The Lives and Loves of Daisy and Violet Hilton: A True Story of Conjoined Twins (Random House, 2006), that I was able to get this biographical sketch of Moskov:

|

| Jensen's book |

A movie man of long, rich, and varied experience, Moskov had apprenticed with the highly regarded producer Lewis Milestone. In the late 1930s, Moskov launched his own career as a producer, shepherding the development of such solid hits as Angel Island (1937), Joe Palooka, Champ (1946), Isle of the Missing Men (1947), Heading for Heaven (1947), and Search for Danger (1949). Only months before he was approached by [idea man Ross] Frisco, Moskov had completed Champagne for Caesar, a sparkling, critically well-received comedy about radio quiz shows. The film featured such A-list stars of the day as Ronald Colman, Celeste Holm, and Barbara Britton, and boasted a score by Dimitri Tiomkin. It was perhaps surprising that a producer of Moskov's credentials would agree to participate in a film project as amorphously defined as Frisco's Chained for Life. He may have been impressed that the sisters themselves were entirely underwriting the project and that he would be spared the responsibility for raising any of the production costs.

Author Dean Jensen then goes on to describe the screenwriter of

Chained for Life, Nat Tanchuck (1912-1978), who is also the credited screenwriter on

Married Too Young:

A graduate of the University of Southern California, Tanchuck worked as a newspaper reporter, a short story writer, a movie reviewer for trade publications, a public relations flak, and a developer of scripts for radio and television. But at the time he was tabbed by Moskov, Tanchuck could only claim credits as an assistant writer on three pictures, all of them forgettable: Federal Man, I Killed Geronimo, and Timber Fury. Moskov was probably not in a position to attract a more seasoned writer for the project.

The relative novice Nat Tanchuck must have done something to impress producer George Moskov, since they worked together a decade later on another film -- that is, the one we're covering this week. For the most part, though, Tanchuck stuck to the small screen, penning lots and lots of TV Westerns, including episodes of such ratings titans as

The Virginian, Bonanza, and

Wagon Train... as well as such slightly less-remembered oaters as

Fury, The Adventures of Jim Bowie, and

The Restless Gun. By the time

Married Too Young rolled around, director Moskov would have been in his late sixties, while writer Tanchuck would have been approaching 50. Neither had any experience in writing youth-oriented films at all. Is it possible, then, that these men sought the input and guidance of Edward D. Wood, Jr., who would have been a relatively youthful 38 and had at least some background in teen-sploitation? Well, that's the going theory. Let's examine the case up close, eh?

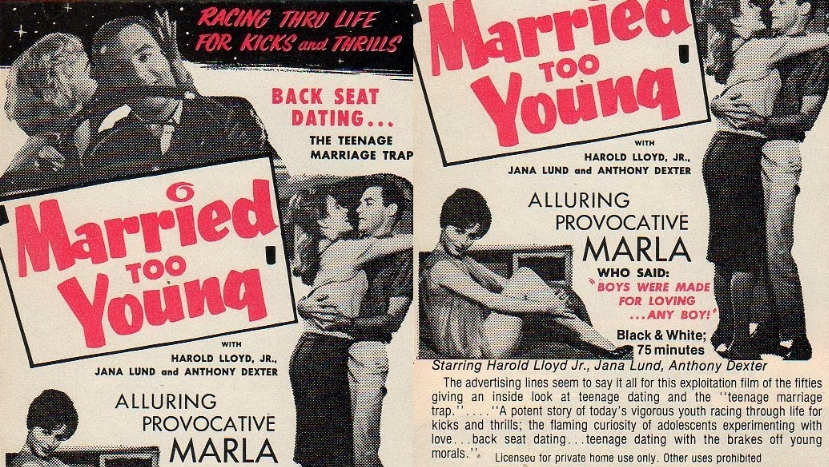

M A R R I E D T O O Y O U N G (1962)

|

| Apparently, this was a big issue back in 1962. |

Alternate title:

I Married Too Young

Availability: That's sort of a bugaboo when it comes to this film. There have been a few VHS editions of the film, including releases from

Hollywood Home Theater and Sinister Cinema, but these are out of print. Sinister later put this film out as a DVD-R, but the company no longer lists the film on its website. A Retromedia DVD release was supposed to have happened in the 1990s, following on the heels of Tim Burton's

Ed Wood, but nothing whatsoever seems to have come of this, other than a trailer (which you can see on the

Big Box of Wood DVD collection).

Filmmaker Fred Olen Ray has recently promised via Facebook that

Married Too Young is "coming to DVD 16x9 from the original 35mm negative this year." In the meantime, if you are truly horny to see this flick, I will direct you to

the Video Beat, a Something Weird-esque company that specializes in DVDs of vintage rock movies and TV shows.

Their edition of the film ($19.99) comes complete with a few trailers and a 1966 episode of

The Donna Reed Show featuring guest star Lesley Gore.

The backstory: Russian-born director? Check. A star whose father is a famous comedian? Check. Early 1960s release date? Check. Socially-relevant, torn-from-the-headlines plot? Check. A bunch of twenty-somethings portraying troubled high schoolers? Check. Uncredited, possibly apocryphal script work by Ed Wood? Checkmate. With all these factors in common,

Married Too Young makes an obvious companion piece to last week's film,

Anatomy of a Psycho. Both films are essentially byproducts of the newfound freedom and autonomy American teenagers attained during the 1950s, as they now had money of their own to spend and free time in which to spend it. Thanks to improvements in technology and a postwar economic boom, young people were, for the first time in the nation's history, building their own parallel society divorced from that of their parents. More than ever, films, magazines, clothing, music and more were being manufactured specifically for kids, with little regard for what their parents might think.

Obviously, many grownups were alarmed about this state of affairs and felt they were losing control of their own children. Thus was born the Golden Age of Juvenile Delinquency, a natural topic for the movies. But while

Psycho dealt with violence,

Married Too Young dealt, albeit obliquely, with an even more uncomfortable topic -- sex -- even though that troublesome word is never once even uttered in the film. And like so many schlock films of the era, the tone of

Married Too Young is dour, preachy, and judgmental, so the filmmakers could always claim that their work was intended as moral instruction rather than crass exploitation.

|

| The newlyweds, Helen and Tommy. |

The plot is very simple. High school senior Tommy Blaine (Harold Lloyd, Jr.) is a part-time race car driver and auto mechanic who aspires to become a doctor. He also wants to go "all the way" with his steady squeeze, rich girl Helen Newton (Jana Lund), but they know that having sex outside of marriage is wrong. So they zip across the state line, where the Justice of the Peace (David Bond) is only too happy to unite them in holy matrimony. Helen's snooty parents (Trudy Marshall and Brian O'Hara) are aghast at the news, and Tommy's working class slob parents (Nita Loveless and Lincoln Demyan) aren't too thrilled either, but they're stuck with the unfortunate situation.

The young marrieds try living at Tommy's house, which doesn't work, then at Helen's house, which is worse. After Tommy gets a modest raise from his boss at the garage (George Cisar), he decides to buy a house for himself and his bride, but he quickly gets into serious debt. So against his better judgment, he gets involved with a slimy gangster appropriately named Grimes (Anthony Dexter), who hires him to modify then deliver stolen cars. Not too long into this assignment, Tommy manages to attract the attention of the cops and, in his panic, drives himself and poor Helen over a cliff. Barely scratched, Tommy and Helen go to court, where a benevolent judge (Richard Davies) releases them into the custody of their parents, to whom he gives a stern lecture about the importance of love and understanding. The end.

|

| Heather Tanchuck |

But how, exactly, does Edward D. Wood, Jr. fit into the picture? Did he work on

Married Too Young at all? Well, Heather Tanchuck, the daughter of credited screenwriter Nathaniel "Nat" Tanchuck, has some very strong opinions on the subject, which she expressed to

an Ed Wood fan site through e-mail. To wit:

The movie Married Too Young was NOT partially written by Ed Wood. My father, Nathaniel Tanchuck, wrote the entire movie, and I would truly appreciate this if you would correct your site. I was a child, I have a copy of the script, I visited the movie set. Ed Wood worked at Hal Roach or some other studio at the same time as my father, but my dad, Nathaniel Tanchuck, is the only writer of Married Too Young.

|

| Weldon's film guide. |

Is she right? Married Too Young is not included in Rudolph Grey's exhaustive

Nightmare of Ecstasy: The Life and Art of Edward D. Wood, Jr. None of the interviewees even mention George Moskov or Nat Tanchuck. And Ed didn't include the film in his own self-curated list of movie credits that he presented to Fred Olen Ray. But the film is nevertheless indexed in Ed Wood's filmography at both the

Internet Movie Database and Phillip R. Frey's

Ed Wood Online site. It also receives a full write-up in Rob Craig's

Ed Wood, Mad Genius: A Critical Study of the Films, where it is sandwiched between

Revenge of the Virgins and

Shotgun Wedding in the "Sexploitation Superstar" chapter. And in his seminal book,

The Psychotronic Video Guide to Film (Macmillan, 1996), critic Michael Weldon says, "Apparently, while Ed Wood was making

The Sinister Urge for Headliner Productions, they had him co-write this very dated movie about overage 'teens.'"

The Video Beat's DVD of the film also plays up Ed Wood's involvement, and it seems likely that any further life

Married Too Young may have is due entirely to its connection to Wood. Rob Craig's book traces the attribution to

Sinister Cinema, the film's erstwhile home video distributor: "According to Greg Luce at Sinister Cinema, a producer for Headliner Productions claimed that Wood was brought in to finish up the troubled production, and can be credited with the last 15 minutes or so of the completed film."

Ed Wood did work for Headliner on multiple occasions. That company produced two iron-clad, bona fide Ed Wood movies:

The Violent Years (1956) and

The Sinister Urge (1960). Craig concentrates his critical attention on those last 15 minutes and finds within them several Wood-ian motifs, including a "bizarre dream-montage," plus "the miraculous 'resurrection' from certain death of the heroes," and a "stern moral lecture." The critic concludes: "Surely, the spirit of Ed Wood hovers over this final reel of

Married Too Young." It may or may not. And don't call me Shirley. (Could Craig, in fact, be punning on Ed Wood's drag name here?)

One crucial fact missing from the film's opening titles is the name of its producer. We are merely told that

Married Too Young was "produced by Headliner Productions, Inc." Roy Reid was the producer of

The Violent Years and

The Sinister Urge, but his familiar moniker does not appear here.

|

| Sexy "bad girl" Marianna Hill steals a few scenes. |

The most famous name in the film's credits is easily that of Harold Lloyd, Jr. (1931-1971), youngest son of the famed silent comedian of the 1920s whose

sound films never quite caught on as they should have. Having made a disastrous attempt at a comeback with 1947's

The Sin of Harowhld Diddlebock for director Preston Sturges, Lloyd the Elder was retired by the time his son decided to take a crack at the family business in 1950.

Never a great success, often an outright failure, Lloyd the Younger landed his first big role in his early twenties in the arson drama

The Flaming Urge (1953). From there, he stuck mainly to lowbrow, low-budget fare, such as

Frankenstein's Daughter (1958),

Girls Town (1959), and

Sex Kittens Go to College (1960). His eccentric father is said to have been unusually supportive and forgiving through all of his son's personal and professional pitfalls. Lloyd's private life, in which he overindulged in alcohol and had a penchant for rough gay sex, was infinitely more interesting than any of his films. The bland

Married Too Young was pretty much his last hurrah. After a supporting role in

Mutiny in Outer Space in 1965, he was done. The debilitating effects of a stroke left him unable to work, so there were no further film or TV appearances. A decade after

Married Too Young, Harold Lloyd, Jr. was dead at the very young age of 40.

Lloyd's

Married costar, Joanna Lund (1933-1991), has at least one Elvis movie (1957's

Loving You) on her resume, plus appearances on TV shows like

Dragnet and

Sea Hunt as well as such classic rocksploitation flicks as

Don't Knock the Rock and

High School Hellcats. Villainous Anthony Dexter (1913-2001) was on the back half of his film career when he did

Married Too Young. He'd previously played the title role in the biopic

Valentino (1951). Other notable credits include a couple of

MST3K movies,

Fire Maidens of Outer Space (1956) and

The Phantom Planet (1961), plus the lavish musical

Thoroughly Modern Millie (1967) and the usual slew of TV work.

The most accomplished member of the cast, however, is probably the requisite "bad girl," Marianna Hill (b. 1941), one of the few major cast members who's still alive. This was very, very early in her long and varied Hollywood career -- her first feature film, though she'd already been racking up TV gigs for two years by that point. Hill's credits include the Oscar-winning sequel

The Godfather: Part II (1974) plus

High Plains Drifter (1973) as well as episodes of

Star Trek and

Batman. Given her sultry good looks, it's no surprise to learn that she also worked as a model.

By the way, here's a little delight that recently turned up on an Ed Wood Facebook group: an original 1962

Married Too Young pressbook that was sent by Headliner Productions to exhibitors planning to show the film. It contains some production details about

Married Too Young, as well as newspaper advertisements, radio copy, and suggestions for theater owners who book the film.

Headliner's strategy for hyping the film seems to have been emphasizing the famous family name of its male lead. "Altho Harold Lloyd was a famous comedian to the theatergoers of a generation ago," it says, "his son, Harold Lloyd, Jr., chose a dramatic career in the acting profession." The pressbook declares that

Married Too Young is Junior's "first starring role," which falsely implies that the young man is a newbie.

The "controversial" nature of the plot also merits a mention or two. According to the euphemistic and vague ad copy, our hero faces "the premarital problems leading to a hasty marriage with his high school sweetheart," while the film's plot concerns "young marrieds experiencing marital incompatibility because of uncontrolled biological urges of immature youth." That's an awful lot of words to say that two dumb high schoolers got hitched because they were horny. The film's exploitable auto racing angle, curiously, is ignored. Anyway, enjoy! (Click on the individual pictures to see them full size.)

|

| The Donna Reed Show's cast. |

The viewing experience: Like crossing the length of a football field through hip-deep mud.

Married Too Young is a lugubrious, sluggish film that feels longer than its modest 76-minute running time. It's important to remember that "the Sixties" as we know them hadn't really gotten underway by 1962. The sexual promiscuity, creative experimentation, and hedonistic indulgence we now associate with the decade were still on the horizon, along with zeitgeist-shifting events as the JFK assassination and the British Invasion. The rigid, stultifying morality of the Eisenhower-era 1950s was very much in effect back then. You can see that in every frame of

Married Too Young, which plays like a particularly dour, laughless installment of a domestic TV sitcom.

In fact, that's why it's especially appropriate that the Video Beat chose to pair this flick with a vintage episode of

The Donna Reed Show. Aesthetically, they're very much alike.

Donna Reed ran from 1958 to 1966, and the episode in question ("By-Line--Jeff Stone") turned out to be the series finale, even though it isn't written as one. Everyone is so clean-cut and well-behaved that you'd never guess that the Velvet Underground, Timothy Leary, acid trips, love beads, and

Sgt. Pepper were just around the corner. Donna and her kin had no idea what was in store for them.

To understand

Married Too Young at all, you have to cast your mind back half a century to a time when two teenagers would actually go to the trouble of getting married before having sex. Obviously, they could just skip the marriage and go straight to the sex, but then they'd wind up like the doomed, weeping teenagers in

Too Soon to Love (1960), whose trailer is included on the

Married DVD. In that film, poor Cathy (Jennifer West) is "betrayed by [her] innocence" and winds up pregnant after her out-of-wedlock sexual rendezvous with boyfriend Jim (Richard Evans), who frets, "I'm 17 years old! I'm in high school!" The trailer shows Cathy and Jim visiting an unlicensed abortion clinic run by, of all people, Billie Bird, who is best known for playing sweet old ladies on TV shows like

Dear John and

Benson. As Cathy and Jim ascend the stairs to the clinic, they see another couple coming down. A young man props up his shell-shocked girlfriend, who looks like she's just been through the

Night of the Living Dead. "Oh, God, Jim," sobs Cathy. "I can't!" One might point out that if the youngsters from

Too Soon to Love and

Married Too Young had access to birth control, they could avoid any inconvenient pregnancies and wouldn't have to get married to have sex either. But that's 2010s thinking, not early 1960s thinking.

|

| Anthony Dexter makes time with Marianna Hill. |

Tommy and Helen are squeaky clean, goody-two-shoes characters with very few distinguishing personality traits, so it's difficult to become terribly involved in their story. In his leading role, Harold Lloyd, Jr. is mostly a wholesome dullard, sort of reminiscent of Peyton Manning, but without the quarterback's self-aware humor. Jana Lund is scarcely more interesting, though she does flounce around in a frilly nightgown during a few scenes, a detail that helps build the case for this being an Ed Wood movie. (Eddie, in case you're just joining us, loved such garments and included them in many of his scripts.) And her character, Helen, does get a pretty snappy comeback in one scene. When her mother asks her, "Helen, are you still here?" Helen responds, "I'm not a mirage."

Zing!

Overall, the parents are just clueless authority figures who have no idea how badly they've warped their own children. Helen's mother, in particular, is a snooty socialite whose life seems to revolve around the country club. The fact that she gives her daughter money with which to buy dinner is an early warning sign, especially for anyone who has seen either

The Violent Years or Sam Newfield's

I Accuse My Parents (1944). The oblivious, social-climbing mother seems to be a stock character in cautionary tales of this nature, as does the slick, overconfident gangster who is all too eager to lead naive young people into hellish Faustian bargains. Filling that role here is the unctuous Grimes (played by "guest star" Anthony Dexter), whose very name has a Dickensian aptitude to it, like Scrooge or Gradgrind or Havisham.

Tony Dexter struts through this film like he just won first prize in a bullshitting contest and couldn't be prouder of that fact. When he blatantly steals another guy's girlfriend away from him, he's more concerned that the cuckolded rival will rumple his expensive suit: "This custom-made fiddle set me back a hundred and fifty clams." As far as I could determine, Grimes remains unpunished by the end of the film. In the heavy-handed, moralistic world of Ed Wood, that's a rarity.

The girl at the heart of this little love triangle is

Married Too Young's own personal jezebel, Marla (Marianna Hill), a flirtatious, vivacious vixen who gives the movie its only real eroticism. Marla is also given some of the film's most colorful, slangy dialogue. When the local malt shop owner objects to being called "daddy-o," for instance, Marla casually replies: "Be a rectangle then." Together, Marla and Grimes are yet another example of what I call the "scheming criminal couple," a staple in many of Eddie's films.

What else is there to distinguish this script as Ed Wood's handiwork? Eh, a little bit here and a little bit there. Nearly every reviewer has pointed out the tonal and structural similarities between this film and

The Violent Years, both of which have sermons delivered by judges to neglectful parents. But as Rob Craig points out, such preaching is commonplace in youth-oriented exploitation films. Similar adult authority figures appear in other, non-Wood films, like the aforementioned

I Accuse My Parents and even the cult classic

Reefer Madness (1936), the ultimate cinematic example of innocent youth gone astray.

If anything,

Married Too Young is more liberal and forgiving than most of Ed's other films. Note, for instance, how hard the hammer of justice comes down on the pretty little noggin of the heroine in

The Violent Years. One especially Wood-ian trait I noticed in

Married Too Young, however, is that the characters have a habit of making sweeping condemnations of the opposite sex. Wood's male heroes lamented the inscrutable ways of womankind in

Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959) and

Bride of the Monster (1955)

, and it seems like every Stephen Apostolof film from the 1970s had a "men are bastards!" speech by one of the female characters. Here, both genders are taken to task:

- Tommy: "Women! What's a guy get mixed up with them for?" (This line has special resonance, since the actor speaking it -- Harold Lloyd, Jr. -- was gay.)

- Helen's mom: (angrily, to Helen's dad) "Oh, you men! How naive can you be?!"

- Tommy: (to Helen) "What's with you dames? A fella just wants to dance, and immediately, out come all the cat claws!"

And then, there is the matter of the brief dream sequence, which doesn't occur until the movie is about 80% completed. Surprisingly, since Ed's movies are often considered to be surrealist in nature, you'd think he'd have such scenes in a lot of his movies. But the truth is, he really doesn't go down that particular path very often in his scripts. The actual, day-to-day

waking reality in films like

Plan 9 and

Bride of the Monster is already so skewed and bizarre that a dream sequence would merely be gratuitous. A pedant could argue that virtually the entirety of

Orgy of the Dead (1965) is a dream or fantasy, but that quality makes

Orgy an exception.

The one big dream sequence in the Wood canon, the one that makes further scenes of this nature unnecessary, occurs in Ed's debut feature,

Glen or Glenda? (1953). It is a lengthy, imaginative, wildly free-associative passage that marks a major, jarring departure from the "reality" of the rest of the movie. By contrast, Helen's paranoid dream near the end of

Married Too Young is tame and sensible. But it does bear a passing resemblance to the infamous

Glenda dream. Both scenes rely on the layering of images, with one bit of film transparently superimposed over another to create a gauzy or ghostly effect. And both also employ the taunting repetition of certain words or phrases.

Glenda fans will undoubtedly recall that poor Glen was vexed by the voice of what sounded like a snotty young girl, chanting fragments of the old nursery rhyme about what little boys and little girls are made of. ("Puppy dog tails" and "everything nice," respectively.)

In

Married Too Young, there is a series of blurry images, most of which are projected over the sleeping form of Jana Lund. First we see a bridal magazine, then a marriage license, and then the wedding ceremony itself, with Tommy and Helen once again exchanging "I do"s in front of the Justice of the Peace. All the while, we hear a chorus of adult voices -- I'm guessing these are meant to represent Tommy and Helen's disapproving parents -- repeating a single sentence over and over. At first, the parents speak one at a time. Then they chant in unison. But the phrase doesn't change. There's a lot of echo on the soundtrack, as well as some eerie sci-fi-type music in the background (is that a theremin I hear?), so it's difficult to make out exactly what they're saying. It sounds like: "Now, you get married too young, too young!"* The particular cadence of the actors makes it sound a lot like the "lions and tigers and bears, oh my!" chant from

The Wizard of Oz (1939) or even "They're Coming to Take Me Away, Ha-Haaa!" by Napoleon XIV.

After reading the description of the dream sequence in Rob Craig's book, I was a little disappointed when I saw the movie and learned that the scene only accounts for about a minute of screen time. Such are the hazards, I suppose, when one excavates the dusty, cobwebbed corners of Edward D. Wood Jr.'s filmography. As a souvenir of the morality of another era,

Married Too Young is a somewhat valuable little trinket. Purely as entertainment, it's a real drag, daddy-o.

* It could also be "Now you can get married too young, too young!" or even "How'd you get married too young, too young!"

|

| Here's my visual breakdown of the dream sequence in Married Too Young. |

In two weeks: From here on out, Ed Wood Wednesdays is going to a biweekly schedule. Why? Well, friends, I won't mince words. The cupboard is not entirely bare, but it's sure getting there. I have already covered all the movies reviewed in Rob Craig's Ed Wood, Mad Genius, plus a few more. What's left? Well, if we're strictly talking about movies that involved Ed Wood and were made during his lifetime, then to my knowledge I've reviewed everything that's currently available to the public on DVD and/or VHS. If you know of something I've skipped, please tell me about it. After that, what remains are the posthumous tribute films and documentaries. Movies I could cover include: The Haunted World of Edward D. Wood, Jr. (1996), Ed Wood: Look Back in Angora (1994), Flying Saucers Over Hollywood: The Plan 9 Companion (1992), The Vampire's Tomb (2007), I Woke Up Early the Day I Died (1998), It Came from Hollywood (1980), and Ed Wood (1994). At this juncture, what I really need is some reader input. Do you have any interest in seeing this series continue? If so, what sorts of movies would you like to see included? Let me know in the comments section.

.jpg)