|

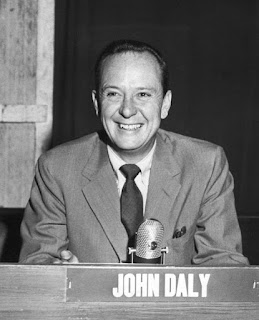

| This pleasant young man somehow wandered onto the set of What's My Line. |

|

| Game show host John Charles Daly |

We hunger for an element of risk in our entertainment. I can't help but think about Dave Chappelle's stand-up routine in which he discusses the infamous night in 2003 when magician Roy Horn was attacked by a tiger during a show in Las Vegas. "That's why we really go to the tiger show, right?" Chappelle says to the audience. "You don't go to see somebody be safe with tigers."

These days, pretaped shows are the norm and live broadcasts are considered special events. This was not so in the earliest days of the medium in the 1940s, when virtually everything on TV went out over the airwaves as it was being made and relatively little was saved for posterity via crude kinescopes. A major change arrived in 1951, when Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz had the foresight to film their sitcom I Love Lucy on 35mm stock, thus ensuring the episodes would be preserved for future reruns.

Over the course of the 1950s, videotape technology improved and became more common in the industry, allowing shows to be shot in advance and edited. This was seen as a potential breakthrough for the medium. On his 1957 record "Tele-Vee-Shun," satirist (and stubborn TV skeptic) Stan Freberg begrudgingly admitted that "videotape may help somewhat." Freberg himself had been a puppeteer on the children's show Time for Beany (1949-1955) and had learned about the hazards of live television when he'd burned his hand during a sketch involving a clown. On a DVD commentary, Freberg recalled that the clown puppet made "a fast exit" from the scene after catching on fire.

By the 1960s, many shows were being filmed or taped in advance, but the venerable panel show What's My Line (1950-1967) was still being broadcast live every week from the CBS studio in New York City. Produced by Mark Goodson and Bill Todman, What's My Line is the kind of stately, old-fashioned program that seems inconceivable to modern day audiences. The premise is very simple. The host introduces a contestant with an unusual occupation, and then four celebrity panelists—generally culled from the theater and publishing worlds—try to determine that occupation (or "line") via a series of yes/no questions. ("Do you work with animals?") The contestant's goal is to stump the panel for as long as possible.

For me, the highlight of each What's My Line episode is the appearance of a celebrity "mystery guest." During this round, the panelists wear blindfolds and attempt to guess the identity of the famous person, again through yes/no questions. ("Are you known for your work in the theater?") This is an exceedingly polite and genteel program, making it truly seem like a relic from a bygone age. The show's stuffiness is now, at least to me, its chief selling point.

On the evening of October 7, 1962, the What's My Line panel consisted of actress Arlene Francis, musician and comedian Victor Borge, journalist Dorothy Kilgallen, and publisher Bennett Cerf. The emcee was John Charles Daly. Francis, Kilgallen, Cerf, and Daly were all regulars on the program, while Borge made occasional appearances as both a panelist and a mystery guest. This would have been his ninth visit to What's My Line, so he was very familiar with the show by then. For the most part, the episode progresses normally. The first contestant is a baseball announcer. The second is a woman who tests razor blades. Typical What's My Line fare.

Things go off the rails only during the final round when Melina Mercouri, a glamorous Greek actress best known for Never on Sunday (1960), appears as the week's mystery guest. The panelists, having dutifully donned their blindfolds, start asking Ms. Mercouri about herself. Dorothy Kilgallen asks the actress if she's in show business. So far, so good. Mercouri smiles broadly and answers yes, but the word has barely left her lips when she is interrupted by a young man in a dark suit who shuffles in front of the camera and describes himself as the show's "second mystery guest." Mercouri looks up at him and meets his gaze, but emcee Daly only gestures vaguely in the young man's direction while talking to someone off-screen.

"Just a moment," Daly says in that calm, measured way of his. "We have a small problem. Gil, will you get the relieving unit in? Schedule two."

|

| A "schedule two" scenario on the set of What's My Line. |

By this point, the camera has pushed in on John Daly, who says, "Well, that's fine. You can talk some other time." He looks slightly impatient, like a man waiting for a slow-running elevator. If he's afraid, he doesn't show it.

Then, in what has to be one of the oddest TV moments of the early 1960s, bespectacled announcer Johnny Olson (the man best known today for his "Come on down!" catchphrase from The Price Is Right) jogs onto the stage, zipping past the panelists and the logo of the show's sponsor, Geritol. The panelists, don't forget, are blindfolded and see none of this. Seconds later, Olson and another man escort the intruder off the set. Yet another man, this one wearing a grey suit, follows quickly behind them.

The camera returns to Mercouri and Daly. The actress repeats her previous answer to Kilgallen's question, but Daly interrupts: "Now, actually, panel, so that you will not be confused, we've had a bad-mannered visitor who has now been removed from the stage, and we can go on with what we were up to." He then restates the rules of the game, and the program continues as if nothing had happened. I'm struck here by Daly's description of the intruder as a "bad-mannered visitor." I've described What's My Line as a polite show, which it is, so this incident is treated not as a breach of security but as a breach of etiquette.

Kilgallen, Cerf, and Francis all ask routine questions of Mercouri, with Daly rushing them along a little, perhaps eager to make up for wasted time. Finally, it's Victor Borge's turn to speak. "Are you alone on the stage?" he asks Mercouri.

Daly answers for her: "No, I'm here, too."

"I realize that, of course," Borge responds, "but they removed somebody." He chuckles, which makes everyone else on stage and in the audience laugh, and the tension is broken. Even Daly lets himself laugh. Borge and the three other panelists may have the least idea of what just happened because they couldn't see the intruder. All Borge knows is that "there are a lot of things going on." Presumably he, Kilgallen, Francis, and Cerf only learned the truth after the show was over.

|

| Paul Jones chimes in. |

Van Horne identified the interloper as one Ronald Melstein and said that the delusional young man was under the mistaken impression that he was the night's mystery guest. The critic reported that she felt "a wave of sympathy" for Melstein, who was escorted to the police station after the show. As for Daly's actions, Van Horne writes: "With typical British sangfroid, he simply asked for volunteers to show the gentleman to the wings. The gentleman was shown—so quickly that the entire incident, observers said, took less than a minute of network time."

Two days later, in the October 10, 1962 edition of The Atlanta Constitution, columnist Paul Jones gave readers the show's official version of the debacle. According to CBS, the intruder was simply an audience member who "had a ticket to see the show" and "somehow slipped backstage." Jones' column points out that What's My Line was being simulcast on CBS radio and that "the radio portion of the show was cut off" when Melstein bounded onstage. Jones says that the intruder was removed from the set by "two burly stagehands." Considering that Johnny Olson was one of the bouncers, that description is a bit of a stretch.

Jones explains that the interloper was "handed over to New York City patrolmen stationed nearby" but that no charges were filed against him in this case. The man was written off as a mere prankster and given a verbal warning. Curiously, the columnist then scolds Daly for not giving the panelists or the audience the full story of who this man was and what happened to him. "This would have eased everybody's mind and it would in no way have detracted from the show."

In Daly's defense, I think he wanted to give Melstein as little satisfaction as possible, so as not to encourage him any further. As for Jones' suggestion that Melstein be brought back as a guest on What's My Line, I think this would have set a very dangerous and irresponsible example. My mind flashes to Robert De Niro as would-be comic Rupert Pupkin, who manages to worm his way onto network television through a berserk kidnapping scheme in Martin Scorsese's The King of Comedy (1982).

Further insight into this strange event is provided by the book Johnny Olson: A Voice in Time (2009) by Randy West. The biography describes the What's My Line episode as "disturbing," which shows how our thinking about such matters has changed over the years, especially since 9/11. According to West, the "Gil" whom Daly addressed during the episode was What's My Line producer Gil Fates. The book includes a quote about the episode from Fates:

"In the control room, [director] Frank Heller yelled, 'Who's that? What's he doing? Get him out of there!' Daly, spotting me bewildered in the wings, said, 'Gil Fates, will you please remove this man from the stage?' I signaled to our announcer, Johnny Olson, and together we moved in. Before 30 million people coast-to-coast, Johnny and I each grabbed an arm and eased the interloper —still into his plug—off the stage and into the custody of the stage doorman, who passed him on to the police."West clarifies that the young man was promoting "a dating or escort service" and that "the audio engineers turned down the input from the on-stage microphones" while Fates and Olson were walking Melstein away from the set. In the episode, the sound only dips out for a few seconds. In retrospect, it's amazing how well What's My Line handles this interruption. No one seems flustered or frightened, just slightly inconvenienced. Apparently, they were prepared for such an occurrence. According to the IMDb, John Daly began using code words when it became clear something was seriously wrong. "Schedule two" was his signal to the crew to cut the microphones and change the focus of the camera.

|

| Ronald Melstein's faculty picture. |

In 1974, still living in the Bronx, Ronald married a woman named Wilma Sirota. In November 1977, he brought a civil suit against the brokerage firm Merrill Lynch at the Office of the Bronx County Clerk. At the same location, he brought another civil suit against the New York Telephone Co. in March 1978, so he may have been lawsuit-crazy for a time. Or maybe he was just plain crazy. Ronald and Wilma Melstein divorced in 1983, and there was some ugly disagreement over visitation rights and Ronald's sanity:

"Under the circumstances herein, defendant's refusal to submit to a psychiatric evaluation was a sufficient ground for denying him visitation rights. We note, however, that this is without prejudice to his moving for modification upon a showing of his willingness to submit to a court-ordered psychiatric evaluation."

Further documentation of the case is here. Ronald's ultimate fate is unknown, but he was still living in the Bronx as of 1999. His last-known address is 3017 Riverdale Ave., only 7 miles away from where he grew up.

As for what Ronald Melstein actually did for a living, it looks like he was a public school math teacher. In August 1957, The Herald News in Passaic, NJ reported that "Ronald Melstein of New York" had been hired by the Clifton (NJ) Board of Education to teach school for $3,700 a year. The article specified that he was one of the 20 new hires that year with a degree. (Seven more teachers were hired without a degree.) In September 1960, The Herald News further reported that Ronald Melstein was hired to teach mathematics at Lyndhurst High School at $4,600 a year.

The 1961 Lyndhurst High School yearbook still exists, and there's a pictured faculty member named Ronald Melstein who looks very much like the man from What's My Line. His bio states that he's a resident of the Bronx, which checks out. He received his B.A. from Long Island University and his M.A. from New York University. The yearbook states that Melstein "is teaching General Math in his first year at L.H.S." His personal motto: "Do unto others as you would like others to do unto you."

How does the 1962 What's My Line incident fit into the bigger picture? It appears that Ronald Melstein grew up in relative comfort in the Bronx, became a math teacher, got married, sued some companies, had at least one child, got divorced, and stayed forever loyal to the borough where he was born. In 1962, a year after taking a job at Lyndhurst High School in New Jersey, he somehow bluffed his way onto a nationally-televised game show, claiming to represent a dating service. Did this service even exist or was this all part of a prank? Did he do this to impress his students? Was he actually delusional, as evidenced by his legal problems down the road? The world may never know.

POSTSCRIPT: Reader Victoria Todd informs me that Ronald Melstein's dating service was very real! In early 1971, New York State Attorney General Louis J. Lefkowitz began investigating numerous complaints into computer dating services, with an eye toward possible state regulation of the industry.

Journalist Roger Mudd filed a report on this subject for The CBS Evening News on January 9, 1971. Among Mudd's interview subjects was one Ronald Melstein, president of Scientific Dating Service. It was Mr. Melstein's view that the investigation would make people afraid to use computer dating services. In a weird way, through this appearance, Ronald made a long-time dream come true. Namely, he got to talk about his dating service on national television -- on the CBS airwaves, no less!

Here's a January 11, 1971 article about the topic from The Times Record of Troy, NY. It doesn't mention Melstein or Scientific Dating Service specifically, but it shows what the computer dating industry was like back then. Frankly, it sounds a little shaky and scammy. And if Louis Lefkowitz investigated the background of Ronald Melstein, he might have been dismayed by what he found.

|

| "Riff raff who don't belong." That's the story of my life. |

I received another update from reader gunner4id, who emailed me a fascinating article from the February 23, 1987 edition of a Hackensack, NJ paper called The Record. Ronald Melstein was busted in 1987 by the Hackensack police. Melstein was apparently using his so-called "dating service" as the front for a prostitution ring. So the attorney general was right to be suspicious. This article, although brief, is packed with drama. It reads like a plot summary of a particularly good Dragnet episode.

|

| A sad fate for Ronald Melstein. |

UPDATE FOR 2024

I never thought I'd get the chance to update this article, but I recently received the following email from Robert Melstein, son of Ronald Melstein:

Hi Joe,

I stumbled upon your post. This is my dad (Ronald). He is still with us, recently turned 94, and lives in New York. What's interesting is that all of these "computer" dating services were arguably ahead of their time - look at all of the apps and online dating which resulted! I wasn't aware that dad had jumped onto the What's My Line? set (I was born much later), but it doesn't surprise me that he would have tried something like that to get attention for his business. As you cited in the post, my mom divorced him and I grew up primarily with her, though I reestablished a relationship with my father in the mid '80s.

How about that, huh? Miracles never cease.

UPDATE FOR 2025

I recently received an email titled "Ronald Melstein update" from reader Joseph Lynn. When I saw the title, I had a sneaking suspicion what the news could be. My hunch proved correct: Ronald died peacefully in May 2025. Amazingly, he lived to be 95. We should all be so lucky. The obituary is very colorful, full of affectionate anecdotes about this eccentric American individual. Some of it, I'd been able to guess through my research. Some was news to me. I encourage you to read it for yourself, and I thank Joseph Lynn for sending it my way.