|

| Tom Keene is Tom Keene in Tom Keene, U.S. Marshal. |

|

| Ed Wood and Tom Keene on the set of Crossroad Avenger |

But then there are Ed's Westerns -- too many in number to be ignored. More of them seem to keep turning up, too. In this series, I've already reviewed Crossroads of Laredo (shot in 1948 but not completed until 1995), the failed TV pilot Crossroad Avenger: The Adventures of the Tucson Kid (1953) with Tom Keene, and two of Eddie's collaborations with would-be Western star Johnny Carpenter -- Son of the Renegade (1953) and The Lawless Rider (1954).

Throughout all these projects, Eddie's approach to the Western genre has been remarkably consistent. He was intent on upholding rather than subverting the standards of the simple cowboy films he grew up on, with squeaky clean heroes, hissable villains, and extremely chaste love interests. In his showbiz primer Hollywood Rat Race (ca. 1965), Eddie decried the rise of morally ambiguous "adult" Westerns and yearned for the black-and-white moral certainty of the old cowboy pictures. (If you want to see Eddie get freaky with the Western genre, you'll have to check out his short stories.)

Recently, a reader named Steve Frisch contacted me to let me know of the existence of another Wood Western: 1952's The Showdown, an unsold TV pilot starring Tom Keene (1896-1963). "I like The Showdown more than any other of Wood's Western films," Steve wrote. "Nice to see with help and money what Ed Wood was capable of." The 26-minute pilot, viewable here, was restored (beautifully) in 2018 by Jeff Joseph of the massive film archive SabuCat. The footage, as provided by Ronnie James, is in remarkably good condition.

Admittedly, this title was almost completely unknown to me. On one of Eddie's mid-1950s resumes, he included The Showdown under his list of "Television Feature Credits," along with Crossroads of Laredo and Crossroad Avenger. Eddie claimed to have written The Showdown for Sidney R. Ross Productions. I can find virtually nothing about Sidney R. Ross or his company, but it's the same outfit behind a couple of other unsold 1950s Tom Keene pilots: Double Noose and War Drums. Rudolph Grey briefly mentions The Showdown in the filmography section of Nightmare of Ecstasy but offers no further details.

Ed Wood's fans will find the credits to The Showdown intriguing because Ed is listed prominently by his own, real name during the opening titles. So, like The Lawless Rider, this is a canonical Wood work with no cause for skepticism. Specifically, Ed Wood and Tom Keene are credited with the original story, while the teleplay was penned by John Michael Hayes. A native of Massachusetts, Hayes (1919-2008) was near the beginning of a long, prominent screenwriting career that would stretch into the 1990s. He's best known for having scripted four of Alfred Hitchcock's films: Rear Window (1954), The Trouble with Harry (1955), To Catch a Thief (1955), and The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956). Hayes even earned an Oscar nomination for his adaptation of Peyton Place (1957).

|

| Alfred Hitchcock with Showdown scripter John Michael Hayes. |

Much like Crossroad Avenger, The Showdown was conceived as a pilot for a weekly Western series for Tom Keene, who'd been a prolific star of low-budget Westerns in the 1930s and '40s. The show would have been called Tom Keene, U.S. Marshal and would have taken place circa the 1880s. One hint of the time period is that the song "Over the Waves," composed by Juventino Rosas in 1888, plays during a saloon scene. As the title suggests, the stoic Keene plays a marshal who patrols a swath of land in Texas near the Mexican border and reports to mild-mannered Col. G.W. Foster (Jonathan Hale) of the 5th Cavalry Regiment. Keene's chubby, comedic sidekick is a Mexican stereotype named Lopez played by Italian-born actor Frank Yaconelli. Keene and Yaconelli had previously worked together in films like Western Mail (1942) and Arizona Roundup (1942).

The Showdown was directed by Derwin Abbe (1903-1974). A New Yorker who often went by the name Derwin Abraham professionally, he helmed numerous Columbia serials in the 1940s before becoming a prolific TV director in the 1950s. His credits there include Hopalong Cassidy, The Cisco Kid, Judge Roy Bean, and Highway Patrol. A project like The Showdown was comfortably in his wheelhouse. The Lopez character, for instance, is very similar to Leo Carrillo's Pancho from The Cisco Kid. (Sample Lopez dialogue: "This is a fine kettle of frijoles!")

Abbe's cinematographer on this project was Harold E. Stine (1903-1977), another Hollywood veteran with a solid filmmaking background. Stine started as a sound engineer in the '30s, moved onto visual effects in the '40s, and finally became a cinematographer in the '50s. Many of his credits are in TV -- The Adventures of Superman, Sugarfoot, Lawman, Hawaiian Eye, Cheyenne, and even the groundbreaking sitcom Julia. But he worked on some very high-profile films, too, including MASH (1970) and The Poseidon Adventure (1972).

With capable professionals like Hayes, Abbe, and Stine on hand, you might expect that The Showdown lacks the stylistic quirks of Eddie's other projects -- the off-kilter dialogue, the erratic editing, the surreal continuity errors, etc. You'd be right. This is a very competent production, one you probably wouldn't associate with Ed Wood if his name weren't in the opening credits. If coherence and normalcy are what you crave in a Wood project, The Showdown is for you.

Just like Crossroad Avenger, The Showdown is intended as a vehicle for Tom Keene, who was both a friend and collaborator of Edward D. Wood, Jr. in the 1950s. Ed was so proud of his association with Keene that he even name-checked the actor in his book Watts... After (1967), published several years after Keene's death. Admittedly, I've never quite understood Keene's appeal. He's handsome enough and speaks his lines clearly in a deep, authoritative voice, but he seems to lack any charisma or self-awareness whatsoever. Like most Wood fans, my introduction to Tom Keene was his role as Colonel Tom Edwards in Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959). In that film, Keene brings an amusing, matter-of-fact blankness to such absurd lines as, "How could I hope to hold down my command if I didn't believe in what I saw and shot at?" Keene is similarly colorless in Wood's The Sun Was Setting (1951).

Ernest N. Corneau's book The Hall of Fame of Western Film Stars (1969) -- a volume Eddie himself is known to have possessed -- gave me a newfound appreciation for Tom Keene. Corneau writes:

Tom was a star who helped mature the Western gradually but gracefully. He made certain that the plots of his pictures were believable and chose to characterize the hero as intelligent as well as a man of brute strength. He toned down the violence without taking away the sense of excitement. Having set the pattern, he introduced a hero who could think as well as fight and, in a short while, this pattern was adopted by William Boyd in the popular Hopalong Cassidy Westerns.

Every cowboy series like this needs a "baddie of the week" for the hero to either shoot or arrest. In this case, it's Killer Carson (Don Harvey), a masked bandit and gunslinger (allegedly "the fastest draw in the West"). Carson's favorite pastime is to provoke others to shoot at him so he can kill them in self-defense, just to watch 'em die. That's technically legal, but the robberies definitely aren't. Plus he's killed some Wells Fargo guards along the way, so Foster dispatches Keene and a very reluctant Lopez to "bring him back alive" from a nearby town called Dry Creek. Lopez is especially disappointed because he and Keane were supposed to go to Laredo for a little much-needed rest and relaxation. But a hero's work is never done.

Dissolve to the local watering hole where we meet Melody (Betty Ball), your typical Western saloon girl with the requisite heart of gold. Carson naturally wants to get his paws all over Melody. ("You and me can burn up this cheap town!") Just about everybody in Dry Creek is afraid of the smirking, swaggering Killer Carson and gives him a wide berth, but a local named George foolishly challenges him and quickly pays the price. The grizzled, elderly sheriff (Lee Phelps) tells Carson to leave town at sundown, but Carson simply scoffs and says he's having too much fun to leave.

Outside the bar, Keene and Lopez plot how to bring Carson to justice. Lopez just wants to gun him down and be done with it, but Keene has a better plan. They'll "turn outlaw" and gain Carson's confidence. This is rather similar to the plot of The Lawless Rider, in which Johnny Carpenter's square-jawed hero has to pretend to be a baddie in order to defeat the villain. (Was this a common ploy in B-Westerns? I'm not schooled enough in the genre to know.)

Lopez is dubious of this plan, but an undaunted Keene adopts the alias Matt Cleaver and demands to join Killer Carson's poker game. Melody recognizes him instantly and almost blurts out his name, but Keene soon gets her to play along with the charade. To me, Keene looks far too neat and tidy to be a convincing outlaw, but he ingratiates himself to Carson with some flattery: "I hear you're faster with a gun than a hungry rattlesnake after a gopher." Keane seals the deal by showing off his sharpshooting skills, and Carson agrees to bring him in on his next job.

Keene then wins $10,000 from a very unamused Carson in a poker game. Our hero later admits to his sidekick that he cheated, but what does it matter? This was the money Carson had stolen during the Wells Fargo job, and now Keene can hand it over to the bemused sheriff. Back at the bar, Carson and his men plan their revenge. They'll use Melody as bait to lure Keane into a trap and kill him.

Our retirement-age sheriff is resigned to his gloomy fate. He'll either have to face Killer Carson in a gunfight or lose his job as sheriff. But Marshal Keene thinks there might be another way. He visits the local blacksmith, played by the legendary Bud Osborne, a key Ed Wood stock player who also appeared in Bride of the Monster (1955) and Jail Bait (1954), as well as Crossroad Avenger and The Lawless Rider. After flashing his badge, Keene convinces Osborne to let him inspect Killer Carson's saddlebags. There, he finds some telltale Wells Fargo money sacks, which will come in handy as evidence when they put Carson on trial for his crimes.

|

| Bud Osborne and Tom Keene square off in The Shootout. |

A distraught Melody arrives at the sheriff's office and tells Lopez all about Carson's plan to ambush Keene in the backroom of the saloon. "Tom Keene was kind to me once," she explains, "and I owe him something." Melody's plan is that she and Tom should leave town together before Carson has a chance to shoot him. Oblivious to all this, Keene is about to walk right into Carson's trap when Lopez shows up at the last second to warn him. A brief shootout ensues, with Keene and Lopez easily wiping out Carson's thugs. Carson himself, however, escapes.

Melody, Keene, and Lopez think that Carson has skipped town for good, but the world-weary sheriff knows better and prepares for an old-fashioned gunfight in the middle of the street. Sure enough, Carson fires a few shots directly into the sheriff's office, knocking a light fixture off the wall. The sheriff is prepared to face Carson directly, but Keene insists on locking the sheriff in a cell for his own protection. To save the local lawman's reputation, Keene disguises himself as the sheriff -- the second alias he's taken on in this show. "With these clothes on and in this light," Keene says, "they'll think it's you." Never mind that the marshal and the sheriff look nothing alike and that no one with functioning eyesight could believe they were the same person.

At last, two minutes before the end, we arrive at the titular showdown. It's shot just the way you'd expect -- with a lot of cross-cutting between Keene and Carson and occasional cutaways to the nervous onlookers watching from the sidelines. Obviously, since this was the first episode of a proposed series, Marshal Keene is triumphant. But, keeping with his image as the thinking man's cowboy, he doesn't just shoot Carson in the gut. Instead, he shoots the guns out of Carson's hands and arrests him. True to his word, Keene hands the prisoner over to the sheriff and assures the townsfolk that the aged lawman is still up to the task.

Like the Lone Ranger, Marshal Keene isn't interested in any compensation for his heroism. The $10,000 should be returned to Wells Fargo, he says, and any reward money should go to Miss Melody. "Oh, well," says Lopez. "I would only spend it foolishly anyway." Keene cheerfully and quickly agrees. Chuckles all around and we fade to black.

|

| (front row from l to r) Lee Phelps, Tom Keene, Don Harvey, and Frank Yaconelli in The Showdown. |

Obviously, Tom Keene, U.S. Marshal did not become a series. But should it have? Did the networks let a potential hit slip through their fingers? Keene admirably strived for realism and intelligence in his scripts, but I can't imagine too many adults finding this material compelling enough to tune in every week. That leaves kids as the only possible audience. That might not have been bad news. After all, Ernest N. Corneau compared Tom Keene to Hopalong Cassidy, and Hoppy's fans were generally children. Would 1950s kids have enjoyed The Showdown? I'm dubious.

At that time, Tom Keene, U.S. Marshal's biggest competitor would have been The Lone Ranger, which ran on ABC from 1949 to 1957. That series had a number of advantages, however. Its hero had a lot of cool, memorable gimmicks: the mask, the secret identity, the theme song, the silver bullets, etc. On the other hand, Keene's character doesn't really have any memorable hooks, apart from his speed and accuracy with a firearm. And didn't pretty much every cowboy star have that? No way would kids find Lopez as exciting a sidekick as Tonto, even though the former can certainly take care of himself in a gunfight.

Finally, we must consider whether Ed Wood's unique voice can be heard anywhere within The Showdown. Like Wood's other Westerns, this story centers around a clear-cut conflict between an unambiguously good man and an unambiguously evil one. But I think that's true of most early Westerns, especially those aimed at a young audience. One might also be tempted to draw a parallel between the saloon scenes in The Showdown and the many scenes set in bars and cocktail lounges in Ed's later films, stories, and novels. Again, though, the saloon is an extremely common location in Westerns of that era. Where better to have a poker game or a fistfight?

Ed Wood's films are also noted for their highly improbable plot twists. Anything like that here? Eh, sort of. It's kind of a stretch that anyone would take Marshal Keane seriously as an "outlaw" for even a second, considering that he changes neither his appearance nor his demeanor. Keane's plan to impersonate the sheriff near the end also seems half-baked at best. But I don't know if any of this gives The Showdown that signature dreamlike quality of Wood's best-known work.

I suppose there are traces of Ed Wood's personality in some of the supporting characters. The character closest to his heart was probably Melody. Tawdry though they are, saloon girls bring a touch of femininity and romance to the Old West. They're certainly the only ones in Dry Creek wearing anything frilly or lacy. In The Showdown, Melody's affections can be bought by anyone with money to spend. She's lived a shameful life and is not proud of her whiskey-soaked past. But Marshal Keane recognizes something salvageable in this woman, and it's implied that the reward money might allow her to start fresh in a new town. That kind of redemption arc might've appealed to Ed.

Then there is our aged, melancholy sheriff, who is certain that he has outlived his usefulness. He seems to have made peace with his own death, even if it comes at the hands of Killer Carson. Death was one of Ed Wood's major obsessions as a writer, a theme he returned to again and again in print and on the screen. More than any other passage in The Showdown, this fatalistic dialogue between the sheriff and Marshal Keane seems particularly Wood-ian.

SHERIFF: So that's what I've gotta do -- face him on the main street at sundown and kill him.(The sheriff leans forward so that Lopez can light his pipe.)KEANE: Sheriff, I don't like to say this, but you don't stand much chance drawing against the Killer.SHERIFF: I know it, Marshal, but maybe God'll be on my side. You see, I'm an old man. If I lose this job, I don't know where I'd get another one. So I've gotta take my chances. Either I'll win and still be sheriff or I'll lose. Then my troubles'll be over.KEANE: Well, you're old enough to know your own mind.

I'm reminded of passages from Eddie's two most famous films. Glen or Glenda (1953), for instance, has Bela Lugosi say, "There is no mistaking the thoughts in a man's mind." Plan 9 has this quasi-poetic narration by Criswell during the funeral scene at the beginning of the film. Note especially the "sundown" motif.

CRISWELL: All of us on this earth know that there is a time to live and that there is a time to die, yet death is always a shock to those left behind. It is even more of a shock when death, the proud brother, comes suddenly without warning. Just at sundown, a small group, gathered in silent prayer around the newly-opened grave of the beloved wife of an elderly man. Sundown of the day, yet also the sundown of the old man's heart, for the shadows of grief clouded his very reason.

What we're witnessing in The Showdown is both the literal sundown of the day and the figurative sundown of an old man's heart. It's quirky little moments like this that make the film a worthwhile viewing for all Wood fans and raise it above the status of a mere curiosity.

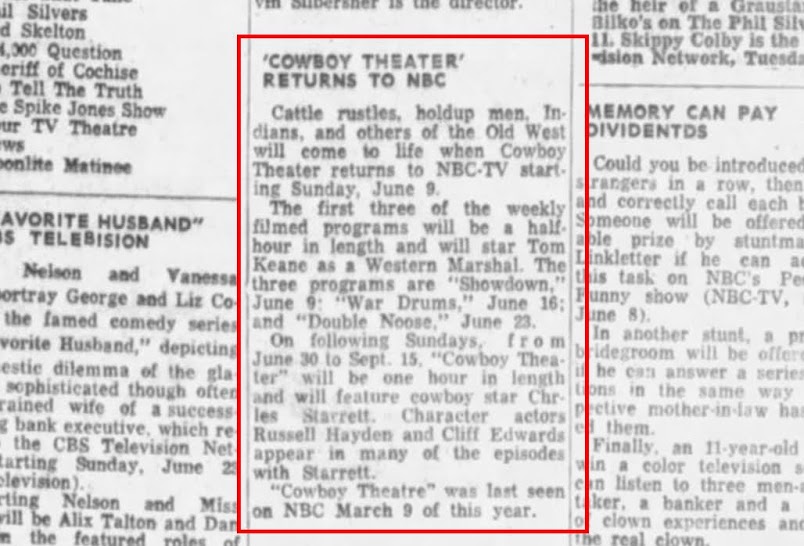

ADDENDUM: Reader Douglas North informs me that The Showdown seems to have gotten at least one television airing after all, alongside War Drums and Double Noose. On June 7, 1957, a Louisiana newspaper called The Crowley Post-Signal ran a brief article informing readers that a series called Cowboy Theater would be returning to NBC on Sunday, June 9. Among the offerings were War Drums, Double Noose, and Showdown. According to the article, these shows "will be a half hour in length and will star Tom Keane [sic] as a Western Marshal." So maybe they were all part of the same series.

|

| The Showdown made it to air in 1957. |

As for Cowboy Theater itself, I can find no record of a nationally broadcast series with that title on NBC or any network. However, numerous local affiliates across America aired programs called Cowboy Theater in morning and afternoon time slots, obviously seeking a young audience. In Crowley, Louisiana, Cowboy Theater aired sporadically throughout the late 1950s on a station called WBRZ-TV, generally on Saturday or Sunday mornings. WBRZ started in Baton Rouge in 1955 as an NBC affiliate and remained with the peacock network until 1977. Today, it still exists as an ABC affiliate.

I am not surprised that The Showdown eventually aired. It is quite competent Western entertainment -- the picture and sound quality are excellent -- and would comfortably fill a half hour on a station's schedule. It is only a matter of time before War Drums and Double Noose surface as well.

No comments:

Post a Comment