|

| Lew Dockstader |

One of the eyewitnesses to the slow-motion train wreck that was Eddie Wood's life is an actor named David Ward, who is quoted frequently throughout

Nightmare of Ecstasy, especially in the sections related to Ed's booze-and-poverty-plagued final decade. Ward also appears as a talking head in such documentaries as

The Haunted World of Edward D. Wood, Jr. and

Dad Made Dirty Movies. In those films, he comes off as gentle, modest, and unassuming -- a polite, soft-spoken fello

w who's just happy to share what he knows.

David Ward's write-up in Grey's "Biographical Notes" is the kind that might catch the attention of someone casually flipping through the book, since weird details stick out from it like rusty nails. "DAVID WARD," it reads. "Stage, television and movie actor. 'My great-grandfather was Lew Dockstader, the minstrel. He gave Al Jolson a job.' A movie based on his life, Edward Ford, is in preparation."

Leaving aside the nearly-irrelevant detail about his great-grandfather, whose stage name is misspelled as "Lou Doxstedder" in Grey's text, this ultrabrief biography raises some obvious questions. Why, for instance, should an actor whose highest-profile assignments were bit parts in films like

Iron Eagle (1986) and

The Limey (1999), be honored with a movie about his life? And why, furthermore, should that movie be called

Edward Ford?

None of this made sense to me until Bob Blackburn, co-heir of Ed Wood's estate, alerted me to the existence of one of the most unusual and, in certain circles, celebrated motion picture scripts never to reach the big screen. This is one of the most rewarding detours I've taken in my seemingly endless exploration of the life and career of Edward D. Wood, Jr., and I'm eager to share it with you today.

EDWARD FORD (1978)

|

The real-life Edward Ford, David Ward, reminiscing with Eddie's widow, Kathy Wood, in the 1990s.

Photo by Bob Blackburn. |

I. Those Pesky Preliminaries

Before we even begin upon the path that will take us into Edward Ford land, a strange and shadowy realm populated by wilder inhabitants than you'll find in any Star Wars sequel, I must point you in the direction of a wonderful article called "The Great American Unproduced Screenplay," which was written in November 2012 for Slate.com by Matthew Dessem. Can you promise me -- I mean, really promise me -- that you will go and read it? It's not a lengthy or difficult read at all, and it will make my job so much easier, because then I won't have to explain so much to you. Matthew Dessem provides a very thorough explanation

of what this screenplay is, why it was written, and what significance it has for him as a work of American literature. Once you learn what Mr. Dessem has to say about Edward Ford, you can return to this article, and I'll tell you what I think of this whole screwy Ford phenomenon. Do we have a bargain? Good. Thank you. So off you go. I'll be right here, awaiting your return.

|

| Screenwriter Lem Dobbs |

Are you back? Good.

While Dessem's article obviously goes into much greater detail, the point is that Edward Ford is a famous unproduced screenplay, considered by many to be a masterpiece. It was written by Lem Dobbs, a successful and opinionated scripter whose credits include Romancing the Stone and The Limey, and dates back to the late 1970s when he was only 19. It is based on his friendship with actor David Ward, a lovably eccentric man who obsessed over movie trivia and tried for decades to break into films himself to no avail. In the 1980s and 1990s, Ward did find supporting roles in films like Iron Eagle, but none of that had happened when Edward Ford was first written. Okay, if you have gotten to this point in the article, you'll probably now want to read Lem Dobbs' screenplay for Edward Ford as well. Here's a link to that, too.

I'm sorry to have to give you so much homework this time around, but sometimes that's just the nature of the beast. It couldn't be helped. Really, what I want to talk about this week is the what the Edward Ford script tells us about Edward D. Wood, Jr. and the subterranean showbiz world he inhabited in the 1960s and 1970s, but in order to get to that stuff, there was a lot of backstory about David Ward and Lem Dobbs that had already been covered brilliantly elsewhere by others.

By now, you should have gathered that Edward Ford is not about Edward Wood, but Eddie -- or, rather, his barely-disguised semi-fictional counterpart, Harold "Harry" Blake -- is an important supporting character in the screenplay, sort of like how Robin Hood is a featured player rather than the star in Ivanhoe. In its own strange way, however, Edward Ford gives us a very insightful and surprisingly complete overview of Ed Wood's life, even though his counterpart character is shunted off to the margins of this screenplay.

II. Oh, All Right. Here's a Plot Summary

The framing story for Edward Ford takes place in Los Angeles in roughly the late 1970s and the early 1980s. It involves a young man, Luke Krantz, who tags along with his eccentric, forty-something companion, Edward Ford, as they go to movies or just drive around town. All the while, Edward and Luke quiz each other on movie trivia (they're both experts), and Luke asks Ed about his past adventures and says he's turning these strange anecdotes into a screenplay.

Ford is a cabbie by vocation and an actor by avocation, but he has long been unable to score the Screen Actors Guild (SAG) card he needs to start his movie career. Instead, he has existed at the very fringe of show business for decades, taking theater roles and occasionally working as a "waiver" (a far-background extra) in the movies whenever possible. Although Luke casually refers to Edward as "a nutcase," he also says the older man is his "best friend" in Los Angeles and genuinely seems to admire his honesty and stubbornness.

Luke starts recording Edward's stories, and it is through these conversations that we piece together Mr. Ford's curious biography.

|

| The Edward Ford diet. |

The Early Sixties. Having freshly arrived from Coventry, Delaware, factory worker and aspiring thespian Edward Ford habitually attends movies in LA's most run-down and dangerous theaters. He has very specific movie-going rules, only attending films that are at least 20 years old and then making meticulous records of actors and titles, which he keeps on typed file cards. And he only goes on Saturday nights. His diet consists of frozen TV dinners.

At his assembly line job, he meets Mitzi, a haggard-looking woman he alone finds attractive, and the two begin an awkward courtship. When he auditions for acting roles, he uses a very hammy and old-fashioned style that merely puzzles casting directors. Although she cannot understand his obsession with file cards, Mitzi agrees to marry Edward, and she moves into his shoddy little apartment with him. One day, by chance, Edward meets two of his all-time favorite B-movie actors, Lester Adams and Jed Dobie, both now has-beens who live in Edward's unfashionable neighborhood. Mitzi encourages her shy husband to strike up a friendship with Jed and Lester, thinking it will help his acting career. Through Lester, Edward meets low-budget filmmaker Harold Blake, a transvestite who throws wild parties attended by all sorts of cast-offs and lunatics.

Edward Ford becomes a cab driver, a profession that he is to hold for many years. His friendship with Jed and Lester continues, too, and he gets his first job as a "waiver" in a major Hollywood studio production. Edward also reconnects with two of his childhood friends from Coventry, both of whom have made their way out to the West Coast. Screenwriter Al Foster is a silver-tongued, bombastic man whose out-of-control drinking frequently gets him in trouble with the law. Artist Ben Krantz, on the other hand, is wealthy and successful. Unfortunately, Edward's relationship with Mitzi is in a downward spiral. She comes to resent the attention her husband lavishes on his precious file cards, and she deliberately tampers with the cards out of spite. One night, able to take no more, she scalds her husband with boiling water. This incident seems to end the Fords' marriage.

|

| The real Lester Adams, Kenne Duncan |

The Early Seventies. Edward, still a cab driver with no SAG card, hangs out a lot with Al Foster and Ben Krantz at Ben's place on Sunset. Ben, a widower, is teaching at UCLA and sleeping with his attractive female students. Ben's young son, Luke, begins to take an interest in Edward, the only person as movie-crazy as he is. Edward's brother, Billy Ford, has returned from a tour in Vietnam and gets romantically involved with the Krantz' au pair, Ilsa. Al is still writing and still drinking and has managed to hold onto a girlfriend, the terminally-depressed Carla.

Because he frequently has to travel as part of his art career, Ben depends upon Edward to look out for Luke. It's no burden, however, because the two are fast friends. Lester Adams and Jed Dobie, however, both die during this time period. Lester, whose death had been erroneously reported on TV a few years earlier, leaves Edward Ford his trademark black hat he wore as a villain in cowboy movies. Harold Blake attends Lester's funeral and waxes nostalgic about the old days.

Edward's acting career has led him to small theatrical productions, including religious plays. His old-fashioned and demonstrative acting style fits in better there. At nights, lonely without a "nice girl" to call his own, he spends his money on worn-out prostitutes. Billy Ford is luckier in love, as he marries Ilsa and moves away from Los Angeles. Edward, however, just keeps on driving his cab, day after day, year after year, always thinking that a successful acting career is just around the corner. As usual, he keeps attending movies regularly, and he stays in touch with Al, Luke, and Ben, with whom he loves to shoot the breeze.

Al, however, returns to Coventry, and Edward is somehow saddled with taking care of the disagreeable and phlegmatic Carla. A working man at heart, Edward Ford spends most of his time in the 1970s in his cab. One day, he is robbed, but the thief is gunned down by police. (This incident is written in a melodramatic style and may be partially a fantasy.)

|

| Edward's Holy Grail: A SAG card |

The Early Eighties. Very little has changed for Edward Ford. He's just a little older with thinner hair now, but his spartan lifestyle -- the file cards, the TV dinners, the fleabag apartment -- is unscathed. Luke remains as fascinated as ever by his older friend, with whom he (reluctantly) goes cruising for hookers. Harry Blake has died, penniless and forgotten, by this point. Edward and Luke pay a visit to Blake's widow, Patty, who seems to have been destroyed by her marriage.

Edward Ford's theatrical career has taken a strange turn: he portrays the token white villains in otherwise all-black productions. Mitzi has remarried, so Edward doesn't have to pay her alimony anymore. Still, Luke and Ben speculate about Edward Ford's financial situation, especially since his employer, the cab company, has gone out of business. He gets by somehow, they agree.

Harold Blake's movies are posthumously rediscovered by hip, young viewers who consider these old films to be campy and unintentionally funny. Luke and Edward attend a crowded Harold Blake retrospective, where Luke gets into the sarcastic spirit of the event while Edward is annoyed and offended by the mocking attitude of the spectators.

In happier news, however, Luke has finished his screenplay based on Edward Ford's life and says that Edward himself can have a role (though not the starring one) in this production, finally giving him a chance to earn his coveted SAG card. When the card itself finally arrives in the mail, Edward stares at it in silent awe. Al Foster, still a hopeless drinker, returns to Los Angeles, and Edward agrees to let his old friend stay on his couch. As optimistic as ever, Al claims he's "gonna make a million" this time around.

III. The Parts About Edward D. Wood, Jr.

|

| The real life Harold Blake |

As you can see from the preceding plot summary, the Ed Wood-inspired character of Harry Blake is a side dish in the

Edward Ford buffet, not the main entree. But this is the weirdest thing: there's basically a complete biopic of Edward D. Wood, Jr. embedded within this script, which is ostensibly about someone else. And it's a damned good biopic, too, both funny and sad, simultaneously grotesque and nostalgic.

Screenwriter Lem Dobbs, the real-world equivalent of

Edward Ford's Luke Krantz character, obviously did thorough research on this project. The depiction of Ed Wood -- apart from one extraneous detail -- is what I'd call tough but fair. It's far less romanticized than the Tim Burton biopic, and it is far less sparing in its depictions of Eddie's demons, including alcoholism and spousal abuse.

But the

Edward Ford screenplay acknowledges the central tragedy of Ed Wood's life: he was simply the wrong guy in the wrong place at the wrong time. Maybe there is no historical or geographical setting in which Ed would have flourished, but ruthless, heartless Hollywood was a terrible setting for a bleary-eyed dreamer like him, especially during a transitional era when the old ways (meaning the studio system with its all-powerful executives and regularly-employed contract players) were crumbling and no one seemed to know where exactly the industry was heading.

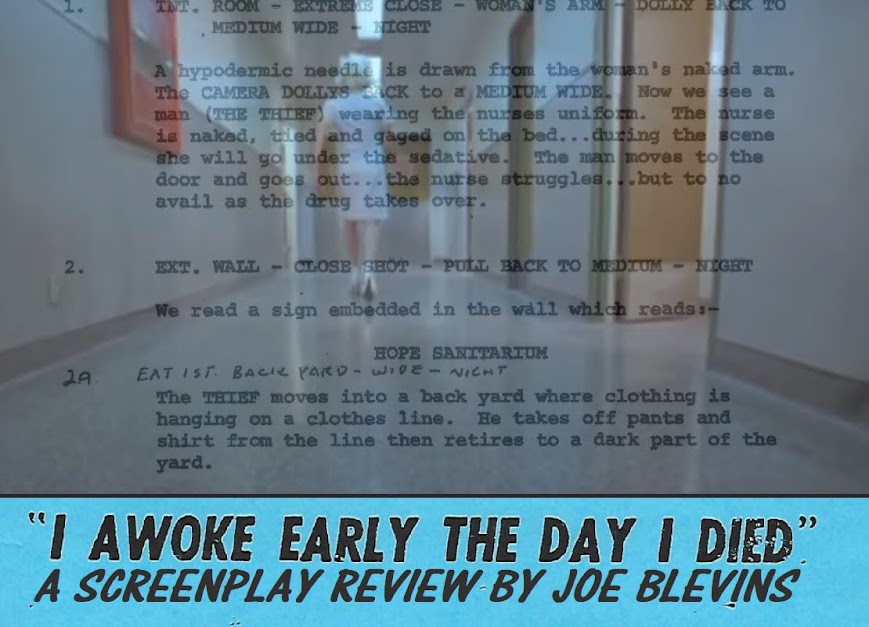

But how much Ed Wood/Harold Blake is there in this screenplay, anyway? Well, as a public service, I've decided to break down all of the sequences involving this character.

(pp. 22-26) Harold first arrives on page 22, hosting a "lively and noisy" party at his home, "a bizarre kind of shack perched on a hillside." The screenplay unkindly describes Blake's guests as "human oddities... strictly grade-Z... the true underbelly of Hollywood society." Edward Ford and his wife Mitzi attend with Lester Adams, the Kenne Duncan-inspired character. Lester supposedly starred in "two or three westerns" directed by Blake, who says he is "trying to raise the finance" for his next picture.

The character of Harold Blake, "a rather dapper man, though slightly pudgy, with a babyish sort of face," is first glimpsed in a bathroom, adjusting the black negligee beneath his otherwise-masculine clothing.

Here is that one extraneous detail I warned you about: writer Lem Dobbs has Harold Blake shooting up heroin in this scene, which Ed Wood never did. He was a drunk, no question, but he had a lifelong disdain for drugs, especially illegal ones.

During this raucous party sequence, we meet two other minor-yet-significant characters: actor Laird Breen, who gives Edward Ford some career advice, and Harold Blake's wife, Patty, described as "not an unattractive woman, actually." Patty, meanwhile, is inspired by Kathy Wood.

As for Laird, my best guess is that he's supposed to be Lyle Talbot, an established actor who appeared in Plan 9, Glen or Glenda?, and Jail Bait for Ed Wood.

(pp. 49-50) Lester Adams has really died this time, and Edward Ford attends his funeral. Harold Blake is on hand to deliver a eulogy: "His old pard Jed Dobie passed on almost exactly a year -- but I don't mourn for either of them. Because I know they're having a heckuva time -- riding the purple sage -- over that final sunset."

In real life, Ed Wood did host a memorial service for the departed Kenne Duncan. From what I've read, it took place around a swimming pool, a colorful detail that failed to make it into this screenplay.

(pp. 66-68) Edward Ford pays a visit on Harold Blake, who "has come way down in the world." Seemingly oblivious to the fact that company is present, Harold openly argues with his wife Patty, whose "looks are all but gone." Patty calls her husband "shithead," an epithet that shows up frequently in Nightmare of Ecstasy as well as in Ed Wood's own short stories from the era. At one point, their argument becomes physical. Typically passive, Edward Ford does not react at all to this.

Fittingly, just like Ed Wood, the Harold Blake character has become a writer of pornographic paperback novels, including Bestial Virgins and Mother's Horny Sons. "I specialize in incest," Blake semi-brags. If the real Eddie Wood had any specialty in the smut racket, it was for stories about transvestites. I can't find any novels or short stories specifically about incest. But this sequence does an excellent job of describing what Ed Wood's life and marriage were like by the 1970s.

One great detail: Blake is "wearing a dress, but hasn't shaved in a day or two." This quirk is substantiated by so many anecdotes about Ed Wood, including those by Ed De Priest and Stephen C. Apostolof.

(pp. 85-86) It's now the early 1980s, and Harold Blake has died. Luke Krantz tells Edward that he's found "an article here about that idiot director you knew -- the one who collected weirdos." Edward Ford bristles when the article refers to Blake as a "primitive." Luke expresses genuine curiosity about this departed director and wants "to see what he married."

And so, with young Luke in tow, Edward Ford respectfully pays a visit to Patty Blake, "a destroyed old hag" who lives in a dog-shit-strewn, "bottom of the barrel" Hollywood apartment. There is a fuzzy black-and-white TV in one corner and garbage scattered everywhere. Patty is glad to see Edward. "This is a good guy," she says to Luke. The younger man is so taken aback by this scene that he's still thinking about it while having lunch with Edward Ford later in the day.

(pp. 93-102) This is, by far, the longest and most complex sequence involving the Harry Blake character. Luke convinces Edward to attend a Harry Blake Film Festival at LA's famed Nuart Theatre. The event turns out to be way more crowded than Edward had anticipated and is attended by smart-alecky hipsters who are only there to mock the late Harry Blake.

The festival is hosted by "two bearded types wearing glasses and 'Invaders' T-shirts." These guys, I guess, are supposed to be Harry and Michael Medved. They sarcastically describe Blake's films in pretentious, pseudo-intellectual language. Another guest at the festival is actor Laird Breen, who genially explains that Harold Blake "was proud of what he did... no matter how crappy it looked."

The films on the bill, all cognates of real Ed Wood productions, are The She-Male (1956), Invaders From Planet Ten! (1958), and Bride of the Crocodile (year unknown). The special effects, dialogue, and acting are all held up for ridicule.

To emphasize the horror of the situation, Lem Dobbs' screenplay intersperses scenes from Blake's movies with flashbacks to the last, desperate years of Blake's own life, during which he was constantly intoxicated, dead broke, and fighting with his wife. Luke gets into the spirit and starts laughing along with the hipsters, but Edward Ford is outraged and offended.

Afterwards, Ford angrily explains to Luke that the two bearded men got their facts all wrong. Bela Lugosi's scenes for Plan Ten, for instance, were shot years before the rest of the picture, and Harold Blake was the star of The She-Male, not a mere bit player. Luke says he'll never watch another Harold Blake movie again.

So there you have it.

If

Edward Ford were made into a two-hour movie, the parts about Harold Blake/Ed Wood might take up twenty minutes. And yet, within those twenty minutes, you'd have a pretty good overall portrait of how Eddie lived his life in Hollywood. Harold Blake's film career and writing career are both represented, and when Harold himself pops up every twenty pages or so, you get a series of vignettes that reflect how this man's life deteriorates alarmingly over the course of two decades.

Just about all the facets of Ed Wood's personality are here: the cross-dresser, the cowboy, the dreamer, the dirtbag, the life of the party, the lush, etc. Only the war hero ex-Marine is absent. In this script, you see the man who smacked his wife around when he was soused, but you also see the man who befriended all the other oddballs in Tinsel Town and gave them work when no one else would.

Edward Ford even takes time to dissect Ed Wood's strange, posthumous quasi-fame.

The people who exploited Ed's name and work are depicted as vultures, nibbling away at his corpse. We also get to meet fictionalized versions of some key people in Ed Wood's life, including the long-suffering Kathy Wood and the foul-mouthed, self-aggrandizing Kenne Duncan. The manner in which these characters are depicted in Lem Dobbs' screenplay is eerily close to their counterparts' portrayals in

Nightmare of Ecstasy, right down to the way they talked. This helps lend Dobbs' script a sense of authenticity.

The only serious misstep, as I mentioned earlier, is the depiction of Harold Blake as a heroin junkie. It's the one detail that is blatantly fabricated, and it's practically first thing we learn about the character!

IV. What's My Take On All This?

"Drama depends on a story being about the most important thing that ever happened to this person."

-Lem Dobbs, author of Edward Ford

|

| Terry Zwigoff, the ideal director for Edward Ford. |

Ever since Bob Blackburn introduced me to Edward Ford, I have read through the script in its entirety at least five times straight through, as if it were a novel. I can imagine myself reading it a couple of times every year and discovering or rediscovering little details in it each time. It's that kind of work: an obvious labor of love positively teeming with baroque little details worth savoring again and again. Even if Edward Ford never passes in front of the cameras, it deserves to have a long life as the kind of screenplay people recommend to one another and pass around among themselves. That would be a very fitting destiny for it.

Naturally, there has been a lot of speculation about this script becoming a "real" movie, and if that ever happens, I think the guy to do it is Terry Zwigoff. Terry's been one of several directors "attached" to Edward Ford, and tonally, it's rather close to the director's humorously dark, endlessly enigmatic documentary Crumb from 1994.

Both Crumb and Edward Ford are about the insular, secretive world of obsessive, nostalgic nerds who are so tuned into their own private wavelengths that they seem to the rest of the world to be borderline autistic. Cartoonist Robert Crumb carefully files away his 78 RPM jazz and blues records with the same care that Edward Ford gives to his file cards of actors and movies. And both films fully explore the surprisingly diverse sex lives of their title subjects!

As for who should play Edward, well, I couldn't help but picture him as looking and talking like a chemistry teacher I remember from high school, but I think Crispin Glover comes as close as anyone to embodying the Ford-ian spirit. The director may have to give Crispin a lot of sedatives though, as one of the hallmarks of the Edward Ford character is that his demeanor almost never changes.

|

| Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. |

In his write-up about Edward Ford, Matthew Dessem deems the script a classic of American literature and repeatedly compares it to F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby. A few paragraphs back, if you'll recall, I compared it to Sir Walter Scott's Ivanhoe. Structurally and thematically, however, Edward Ford bears a closer resemblance to Don Quixote than it does to Gatsby or Ivanhoe. Cervantes' famous, self-styled knight errant overdosed on books about chivalry, fashioned a crude suit of armor for himself out of household objects, and then set out for a series of disastrous adventures, trying in vain to recapture the spirit of an earlier, more romantic age, only to meet with bewilderment and scorn from the people of his own time.

Edward Ford, likewise, overdosed on cheapie Westerns and gangster pictures made by notoriously cut-rate studios like Monogram and PRC and then decided to move to Hollywood in order to find work as a villain in these very kinds of movies, regardless of the fact that they were not being made anymore by the 1960s when he arrived. Like Don Quixote, Edward Ford is episodic, stringing together a series of tragicomic skits about its title character's ill-fated yet strangely noble sallies into an unforgiving world.

Every Quixote needs his Sancho Panza, and in Edward Ford, the sidekick role is filled by young Luke Krantz, a friend's son who becomes a companion, unlikely soulmate, and (ultimately) biographer of the protagonist.

Sadly, the qualities that make the Edward Ford screenplay so great are the same ones that -- I am all but certain -- would make it a complete financial failure as a film. Critics and cinema geeks would love it, but I doubt that rank-and-file ticket-buyers would embrace it. To borrow a phrase from writer-director John Waters, Edward Ford would be one of those "films that get you punched in the mouth for recommending them to even your closest friends."

Most viewers will wonder why the hero of Edward Ford isn't more "dynamic" or why the screenplay leaves out most of those crucial story beats we have come to expect from every single motion picture. Other than having Edward's SAG card as a MacGuffin, sort of like his own personal Holy Grail or Maltese Falcon, this story barely resembles a typical motion picture scenario.

Even though I spent several paragraphs describing the "plot" of Edward Ford, this is not a story-driven screenplay at all. Most of it is about those in-between moments of life: waiting in line at the movies, hanging out with friends at a diner, watching your clothes get sloshed around at a laundromat.

One of my favorite little details in the script, for instance, is a typically overlapping conversation between Al, Ben, and Edward in which they discuss the differences between the words "mongrel," "Mongol," and "mogul." What is actually accomplished here? Not much, except getting to know these three guys a little better and see how they interact with one another.

That may not be enough for some people. In my research for this article, I came across this disheartening 2010 screenplay analysis of Edward Ford by a purported "expert" in the field. If you truly want to know why Lem Dobbs' script never got filmed and seems doomed to remain in limbo forever, I'd recommend reading this article and then the comments below it. Sad but true.

V. My Chat with the Real David Ward

|

| The man himself. |

In January 2015, through the kindly intercession of Bob Blackburn, I was able to talk for about half an hour via telephone with David Ward, the actor who served as the real-life inspiration for Lem Dobbs'

Edward Ford. Not only is the title character based on David, but the incidents in the script are all events taken from David's own life.

How close is the script to reality? Based on my conversation with Mr. Ward, I'd have to say it's pretty darned close -- much more accurate, in fact, than the script for

Ed Wood, which freely embellishes upon the historical record.

Edward Ford, on the other hand, is more like

Dragnet. The story is true; only the names have been changed to protect the innocent. So David Ward became Edward Ford, Lem Dobbs became Luke Krantz, Kenne Duncan became Lester Adams, Ed Wood became Harold Blake, and so on.

Talking to David Ward is no easy trick, I can assure you. Now in his early 80s, he resides in a Los Angeles convalescent home. I spent the better part of a Saturday afternoon trying without success to reach his room. The phone would ring and ring, but no one answered. I think, in all, it took about eight hours before I finally connected with Mr. Ward. I don't want you to think that I sat by the phone all day, wearing my dialing finger down to a nub by calling over and over. I mean, I went grocery shopping and did laundry, too, that day. But every couple of hours, I'd try the number again. And good things, as we all know, come to those who wait. Eventually, I heard a deep, calm voice on the other end.

As it turns out, David Ward is a cheerful and cooperative man whose memory is still pretty sharp.. or sharp enough for my purposes anyway. My interviewing skills are worse than non-existent, so I mostly stuttered and stumbled my way through a vague, general conversation about Ward's life and the

Edward Ford screenplay. Mostly what I wanted to know was, "Did all this stuff really happen?" And he confirmed it all, one seemingly impossible incident at a time.

I think, of all the stories in the screenplay, the one that shocked me the most was the one about David's (or Edward's) wife scalding him with hot water in a fit of pique. But it happened, along with all the other goofy goings on. The stories about Ed Wood I already knew to be true, and I was glad to learn that Lem Dobbs had gotten his facts right in this department.

We even talked about something that doesn't come up in

Edward Ford: David's working relationship with Stephen C. Apostolof. Though these titles don't appear on his IMDb page, David was an extra in the nightclub scenes from

The Cocktail Hostesses and

Drop Out Wife, which were filmed simultaneously.

We talked, too, of Eddie's doomed film adaptation of

To Kill a Saturday Night, which would have paired David Ward with John Carradine. (A real shame that one never came to fruition.)

Mostly, David seems to be proud of his longevity. He pointed out to me that he is probably one of the last people alive who knew Ed Wood personally. Ward specifically referred to the relatively recent deaths of such Wood associates as Paul Marco and Vampira. They're gone, but David Ward is still here.

I can't help but think of that scene from

Citizen Kane in which Jerry Thomspon (William Alland), a reporter for

News on the March, goes to interview one of Charles Foster Kane's business associates and friends, Mr. Bernstein (Everett Sloane), in hopes of finding out the meaning of Kane's last word, "Rosebud." Bernstein can't decipher "Rosebud," but he does act as a keeper of the flame for his departed friend. As Roger Ebert pointed out in his DVD commentary, Bernstein hangs a portrait of Kane over an actual hearth with a fire crackling away inside it.

In a way, that's David Ward's role in the Ed Wood saga. All these years later, he's still tending to that flame of remembrance, making sure it doesn't flicker out. At least not on his watch.